One of the aspects of being elected Mayor in New Westminster (or in any of the 11 municipalities in BC with a local police force) is you are also made the Chair of the New Westminster Police Board. A peculiarity of this is that people commonly are elected to mayor after building experience on City Council, there was a chance to “learn on the job”. That opportunity simply doesn’t exist for police board – in BC, members of city council are forbidden from serving on police boards. So compared to council, the learning curve is sharp.

I have taken the opportunity to take some training from the Ministry of Public Safety that is available for all police board appointees, and have years of experience serving on and chairing various boards, but police boards are unique structures, and we are in a time of significant change in police governance in BC. So I took the opportunity to attend the annual conference of the Canadian Association of Police Governance and engage in some intensive learning and peer networking. I thought I would share here some of my experience and thoughts.

The event was attended by police board members from around the country (though, not Newfoundland and Labrador, but I’ll talk about that later), along with police leadership (both Chiefs and Association leadership), staff, and several academics and representatives from service agencies that interact with police. One thing I learned was about the vast difference in police governance models across Canada, and how in many ways BC is “ahead of the curve” on governance.

”Federal Government has the money, Provinces have the jurisdiction, Cities have the problem”

There was a lot of conversation about the current state of policing across Canada, including discussion of the recommendations arising from various reports looking at policing failures: Turning the Tide Together, Inquiry on the 2022 Public Order Emergency, Reclaiming Power and Place, and others. It was not always clear or consistent what a police board’s role in police reform is. More philosophically, there was some question whether boards, being part of what needs reforming, can at the same time be the agent of that reform.

As board structures vary across Canada, they also vary in the resources available to them, and in the level of political influence in their operation. Most boards have dedicated staff who report to them, not to the police service (something we do not yet have in New West). It was apparent from discussions with board members from other provinces that appointments are distinctly political in many jurisdictions – to the extent that a provincial election ushers in new board members to match the partisan leaning of the new government (something I have never sensed in BC, where most appointments are based on recommendations from the civil service through CABRO).

One thing seemed pretty universal: the recognition that reform (at the minimum) is needed in policing and police governance if we are to turn the tide on declining public trust in policing. To be clear – most Canadians do trust and respect policing, however when one panelist asked the hundreds in the audience “How many of you think we are on a good path right now?”, not a single hand went up. Not one. It seems the prevalence of “bad apple” events popping up across the country, made more visible by social media expanding events beyond local regions, is leading to conversations everywhere about whether those apples all point to a problem with the orchards or the soil (a metaphor stretched many times in this conference). This perception, as much as the reality, has the potential to impact the operational effectiveness of police, as retirements and recruiting are challenging this sector as much as any other. One compelling question was whether Peel’s 9 Principles would be the same if written today, maybe an exercise for police boards to engage in with their members.

”Keep politics out of policing”

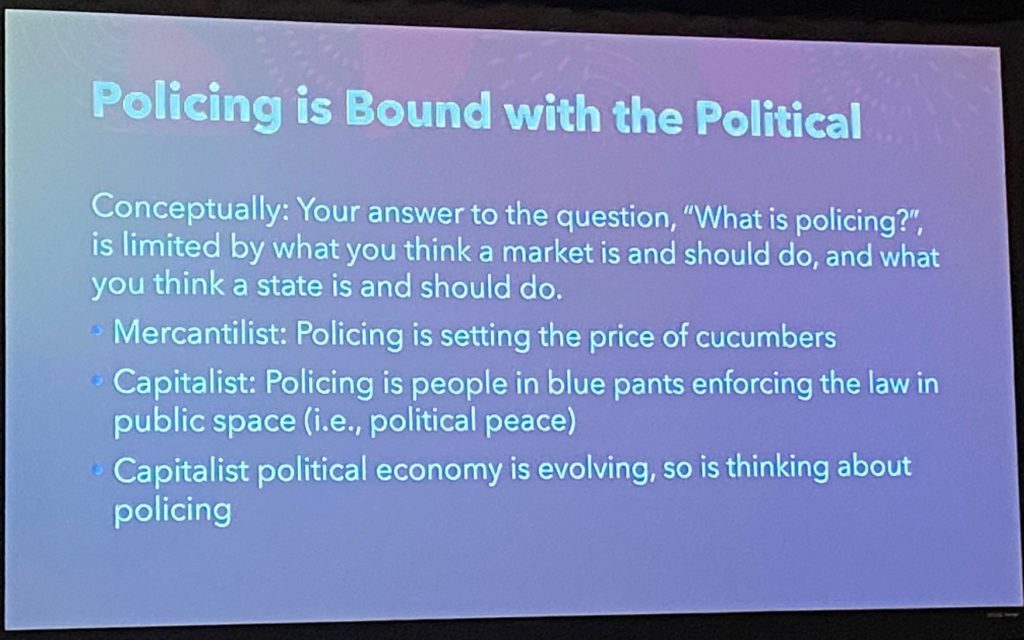

It could be said police boards are where policing meets politics, because police boards are meant to represent the public and be the governance oversight of the public service that is policing. Governance and public representation are inherently political activities. In the panel on Politics of Policing, this was explored at some detail. I especially enjoyed the academic Michael Kempa taking us back to core principles of political economics:

The general discussion here evolved from the simplistic separation of policing from politics to how police boards need to assure transparency and accountability to the public, something they are generally not good at because of the slightly arcane nature of their existence. Police boards are not elected, and as it is unclear if or how they can be fired or reprimanded, it is unclear about how the public can hold them accountable – what is the mechanism available to the public (or for that matter a City Council, the Provincial government, or a police service) to hold a group of volunteers accountable when most of the public don’t even know they exist? This is part of the drive for governance reform.

As a bit of an aside, I found it interesting that the former president of the Vancouver Police Union was on this panel, but the notion of keeping police out of politics was never raised. Last municipal election saw active participation of police associations in the elections of the mayors of BC’s two largest cities, suggesting the “firewall” between politics and police is at best a one-way mirror.

”Speaking as a policing researcher, I can tell you one thing about data: all police data is terrible.”

My absolute favourite session of the conference was a lengthy discussion and participatory exercise about the “Alignment Gap”. This is the lack of consistency between what police leadership say policing values are, and what police members actually do. Police publicly embrace equity, diversity, and inclusion, but are still being found to fall short of delivering on those plans. Police speak of the importance of community, but are too often accused of lacking civility on the ground. In their extensive study of this “gap”, the presenting academics (Hodgkinson and Caputo) suggest the issue points back at strategic planning failures and a lack of involvement of police members in visioning the direction of policing. There is a reluctance in policing to talk to the folks “at the coal face” about the small nuisances and larger challenges in their work. This is partly because of the inferred separation of police boards (who do strategic planning) from the operations of police.

For context: one thing driven into police board members frequently is that our job is strategic planning, policy, oversight, but that operations of police are the wheelhouse of police management and the Chief. Dr. Kempa (in that earlier session) argued this distinction is blurrier than most realize – that the amount a police board can suggest or instruct operations (outside of arrests, investigation, or charging) is better characterized as a negotiation between the board and the Chief, as the board ultimately has the authority to remove a Chief in the event of conflict.

In the end, this session had some excellent suggestions on how police boards and police can better do strategic planning to close the Alignment Gap, mostly by including the membership and the public in more meaningful ways, and improving bottom-up communications.

“Victoria Police still have a Y2K Committee…”

Yes, that was the biggest laugh of the day, and I’m pretty sure (at least I hope!) it was a joke, but funny because it hits close to the bone around the general resistance to change in police organizations, and the seeming use of bureaucracy to deflect from change.

We had a presentation from the Victoria police on the path British Columbia took towards decriminalization of some drugs (which stood in sharp contrast to a presentation from the Alberta Minister of Public Safety on their anti-harm-reduction approach, which seemed disconnected from recent headlines). We heard about the impact of mental health stigma on the ability for police to get help when they are dealing with operational stress injuries and post traumatic stress injuries. There was a panel outlining the Calgary experience with mental health call diversion, which is best described as “police led and community driven”, as opposed to the PACT or CAHOOTS-type model where diversion removes police from first response.

We also had a compelling and newsworthy panel on the complete lack of police governance and failed oversight on Newfoundland and Labrador – our host community. To see a former police chief, a lawyer who primarily represents citizens suing police, a leader of an indigenous rights organization and a progressive City Councillor all asking for the same thing (modern governance for the Royal Newfound Constabulary), only to be met with silence from a provincial government, demonstrated for most of us in the room not from the easternmost province that things could always be worse.

Overall, I am really happy I was able to attend this conference, and will be taking learnings back to the New Westminster Police Board as we enter a phase of governance review. I was also able to network with members of the Police Boards of Nelson, Abbotsford, Surrey, and other municipalities across Canada, and have a new network of collaborators as I continue to learn this new job.

I would love to see NW Police online reporting portal become something that is actually usable. I record so many dangerous drivers each week my stress levels are insane, but what bothers me most, is knowing justice will never be served to the most dangerous ones, solely because the reporting system is so broken.