I just had the Sustainable Communities equivalent of a Stones fan meeting Mick. I had a chance to meet and hear a talk by one of the major rock stars of sustainable Urban Development.

Dr. Kee Yeon Hwang is the President of the Korea Transport Institute, which is a somewhat unusual organization in the Canadian context: a policy research think tank, populated by academic experts in the field, that works directly for the Prime Minister. Dr. Hwang was visiting Vancouver as a Visiting Fellow in Urban Sustainable Development at the SFU Urban Studies Program. While here, he gave two public lectures, one on the Cheonggyecheon Project, and one on Seoul’s bus transit system. The sharp end of my curling season meant I could not attend the evening lectures, but Councillor Cote managed to arrange a visit to New Westminster for Dr. Hwang, which included a walking tour of the City’s waterfront, and a presentation by Dr. Hwang to members of City Council and City staff in Transportation and Planning. Councillor Cote invited members of the City’s Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee, which is how I got into this great talk. The topic, Cheonggyecheon, is relevant and timely in New Westminster, with all the recent talk of North Fraser Perimeter Roads and United Boulevard Extensions, and the City entering a Master Transportation Plan process.

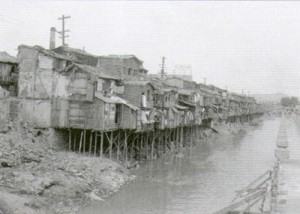

The history of Cheonggyecheon is of a small, ephemeral stream near the centre of Seoul. In the early 20th century, there were less than a million people in Seoul, and this stream was a water source, a place to wash clothes, and an open sewer, much like streams in developing urban centres the world. Things did not improve with the economic collapse around the Korean War. Post-war the stream was mostly home to squatter houses and squatter factories. Between sewage, waste, and dyes from the unofficial textiles industries, the stream was very polluted, and often ran multiple colours. When Dr. Hwang was a child, this was considered the “bad part of town”, with poverty and all the crime that comes with it.

|

| Cheonggyecheon in the post-war period. |

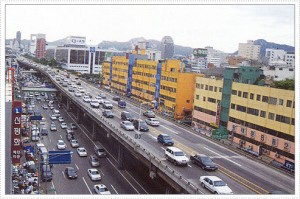

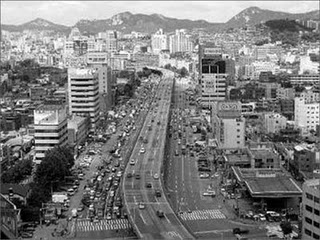

With the rapid development and industrialization of Korea in the 1970’s, there was little resistance to burying a small, heavily polluted, ephemeral stream in the bad part of town, and capping it with 8 lanes or surface traffic and 4-6 lanes of elevated traffic. Seoul was the heart of Korea, and building major freeways was a point of national pride: this is the progress Korea needed to become a leading world economy.

|

| Cheonggyecheon expressway in all its glory. |

???

Fast forward to 2002. Seoul is a modern “world class” city of more than 10 million people. The elevated Cheonggyecheon expressway is congested, the original watercourse has been buried in underground vaults and culverts, and the space between is nothing short of disaster. No sunlight, polluted by vehicles, traffic congested, not accessible to pedestrians as all open spaces are taken up by travelling vehicles, commercial vehicle parking, and unlicensed retail operations (street hawkers). The buildings were aging, and there was no impetus to improve them in this undesirable setting, so the businesses were declining. This was just one of the epicentres of overall urban decay in Seoul. Although they had built the trappings of a modern city, with advanced infrastructure and large dense population, the residents and officials in Seoul were realizing their quality of life – the liveability of their City – was lagging behind cities that were considered “World Leaders”.

This begat a paradigm shift. A new Mayor was elected in 2002, and the new broom swept clean. His new paradigm including shifting from development to conservation; from building spaces for automobiles to building spaces for people; from infrastructure efficiency to infrastructure equality. This is similar to what we now call “sustainability” in urban design. The Mayor immediately announced the plan to tear out the Cheonggyecheon freeway and return it to a 5.8km-long linear park. The project was master planned in less than 6 months, and completed in a remarkable 3 years. There obvious political motivation for the fast timing, in that Mayors in Korea face the polls every 4 years. The project cost almost $300 Million (US), but the planners calculated that this amount was about the same as they would save in 10 years of maintenance of the existing highway and buried waterway system that was reaching the end of it’s design life.

|

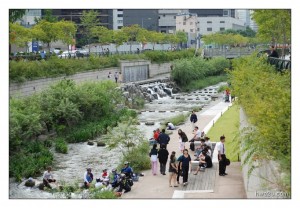

| Before and after airphotos – where would you rather live? |

Although there was an extensive (if rushed) consultation process, including the Transportation Institute, all levels of government, and citizen representatives, this did not prevent significant backlash and protest. The protests will sound familiar to anyone who has listened to the Hornby Street Bikeway project or who might suggest New Westminster might be better off without the waterfront parkade: local businesses worried about losing traffic and customers, concerns about where everyone will park, neighbouring areas concerned that the congested traffic till get worse on adjacent streets. The illegal street vendors were particularly militant in their protests, but the project went ahead.

The road was cut up and removed (with 95% of the material recycled). The stream was exposed and re-contoured. Since most of the stream’s flow was ephemeral and partly because of other water management projects in the City, the stream was going to be dry 8 months of the year. A diversion project from the adjacent river and groundwater sources were combined to provide up to 120,000 M3 of water a day through the stream to maintain a constant minimum of 40cm of water. Storm runoff and combined-flow sewer water was separated and treated before entering the stream. Aside from the base flow, the stream was designed to accommodate the 50-year flood in a lower tier, and the 200-year flood in its upper tier. There were also 22 bridges built to cross the 5.8-km route, although many of there ware actually restorations of original bridges that were partially deconstructed and buried in asphalt in the 70’s.

The end result is 5.8-km people space. Areas are very green and organic, other parts of very hard-surface with lots of facilities to accommodate public gathering, arts, or walking. People are encouraged to interact with the water. Where the symbol of “Korean Progress” used to be a 16-lane freeway full of cars, the new symbol is of urban children playing in a refurbished stream surrounded by green. Paradigm shift indeed.

What of the externalities, and what of the protests? The complaints about increased traffic elsewhere disappeared, just as the traffic did. Ridership on the adjacent subways increased, some people changed their travel times, some changed route, but mostly, people just stopped travelling so much through the area. Adjacent traffic congestion increased less than 1.5%, but overall there was a concurrent 2.5% decrease in Central Business District traffic. Property values adjacent to the stream increased 30%, and businesses prospered as they were suddenly adjacent to a site where there were more than 50 Million visits during the first year. The air temperature in this part of the Central Business District dropped several degrees during Seoul’s hot, humid summers, as the water flow acted as natural air conditioner and created a conduit for cool breezes. All this in a public place for festivals, for lunch, for art, for living space…

|

| One of several “under bridge Art Galleries” |

However, this progress does not forget the past. At several locations along Cheonggyecheon, there are reminders of the past. Those forgetting history are doomed to repeat it.

|

| Several columns preserved, to remind people what they lost. |

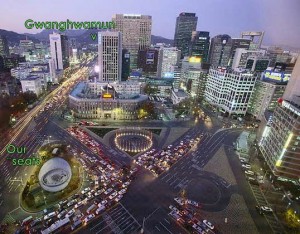

How does this translate to the rest of the City? Once the success of this project was apparent, every part of the City wanted one. Other viaducts have been removed under a “sky-opening” initiative. Other significant public areas in the City have seen the removal of traffic lanes to make room for green space: effectively building for people instead of cars.

?

|

| Seoul City Hall before… |

?

|

| …and after. |

There has been a renaissance across the Central Business District, with more people moving into the area (12,000 new residential units in the CBD being planned right now), greenways popping up in exchange for density across the city, and all of the sudden, people in Seoul are finding they can walk places. With the new mayor talking up plans to refurbish their industrial river front:

Oh, and the visionary Mayor who proposed and fast-tracked this project? He is now the President of the Country.

So… the question is, are we ready in Canada, in BC, in New Westminster, for this kind of shift?

Are we ready to re-evaluate our public space and our public spending? The province is currently spending billions of dollars building more freeways, with little protest. There is huge pressure to push more lanes of “important regional traffic” through New Westminster and along our water front, and people seem indifferent, or think it will solve some problem in a magical way that has never worked anywhere else in the world.

When will our paradigm shift happen? When will we catch up to Korea? Or are we visionary enough now to not bury our waterfront under cars?

Thanks for this summary Pat. I regret that I missed the visit and the talks.

So…. What ?

This is supposed to be visionary ?

So what, did all these people switch to bikes ?

So what, did public transportation take a lead role ?

So what, how man cars are now off the road ?

It’s another smoke and mirror show, it’s not even relevant to the issues we face in the GVRD.

Oh, and if you follow in this guys visionary foot steps you will become president of a Canada !

Anonymous: consistently missing the point, through poor reading comprehension and inability to do her own research.

@speeky – Seoul is a mega city, not once is that mentioned, with a population density of 45k people per square mile, and a population of 25 million. the GVRD has 2 million.

If you where to take the density and shove it in new west’s 7 square miles, there would be 315k people in our royal city, if you can imagine that.

And speeky, if you did read his work, you would have noted “Adjacent traffic congestion increased less than 1.5% “

So did it really solve traffic congestion ?

Now don’t forget… “greenways popping up in exchange for density across the city” so they can fit even more people into new buildings by having a patch of lawn and a tree is called sustainable development ?

This is the direction you call visionary ?

“the existing highway and buried waterway system that was reaching the end of it’s design life.” a demolition ?

“Ridership on the adjacent subways increased” Oh really ? One of the worlds most comprehensive and busiest subway networks, carrying over 8 million a day got even busier!

thanks for all the facts. I can really see how this fits in with your vision. And when will we catch up with Korea’s paradigm shift of increasing density ?

To answer your questions:

1) Yes. 16 lanes of congested traffic removed + negligible impact on surrounding roads = less overall congestion.

2)Yes. Increased density in exchange for preserved greenspace is one model of sustainable development.

3)Yes, removing a freeway was a shockingly provocative move in the middle of a growing industrial city. Look at the protest over removing one lane of Hornby Street. Deciding not to build one in New Westminster would be just as provocative.

4)Yes. Transit ridership in the area went up.

5)I don’t know, but the place where density has to increase first is the burbs that are causing New Westminster’s traffic woes, and to facilitate that, we need to start improving transit service to those areas and stop building freeways.

does “anonymous” want to suggest another region we should learn from? Pot shots from the cheap seats don’t enlighten the debate.

And why should one pursue the holy grail of “solving congestion” problems. Why is not the reversal of decay caused by what was ultimately shown to be an un-necessary freeway not an interesting model to consider?

I wonder how many other un-necessary freeways there are in the world? Maybe we have some in Metro Vancouver? Yet no freeway gets built by being being sold as “un-necessary”.

The only thing I’ve seen to “solve congestion” is an economic recession. But time and time again people driving habits are fostered by the road space made available to them.

@Andrew, So tell me, Oh green one, which town will fare best come this peak oil you all so heavily believe in ?

What problems exist from such high densities of people with so little resources ?

I find it hard to believe the dismantling of a SMALL section of aged infrastructure replaced with a SMALL green space is sufficient to service such densities.

This Dr Kee should have been taking notes from US not the other way around. If Seoul is to be an example of anything, it should be an example of DANGEROUSLY HIGH HUMAN DENSITY.

Just wait till the next global pandemic boys, that’ll thin the herd !