I went on a bit of a rant last week in Council on pedestrian crossings, and it is worth following up a bit here to expand sometimes on the things I rant about. In this case the subject was something we can all agree on – making pedestrian spaces safer in the City – but the details of the discussion outline how difficult it can sometimes be, even when everyone is on the same page. The hill on Richmond Street provides a great case in point about how we want to do things differently, but are stuck with a bad legacy to clean up. And that costs.

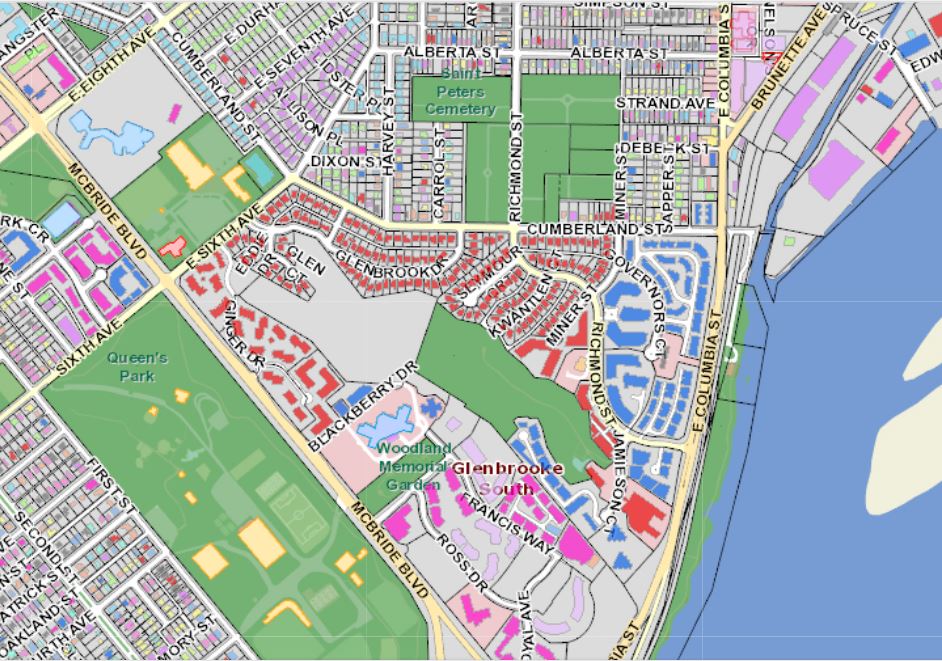

The Fraserview neighbourhood is somewhat unique in New Westminster. Most of our community is based on a well established and dense street grid that reflects how humans move around their communities – a layout that is “human scaled”. The Fraserview neighbourhood was developed out of the abandoned BC Pen site in the 1980s, which was the Canadian peak of auto-oriented suburb design. This is not the fault of the council or staff of the time, or of the people who live there now, but a result of where we were and how we valued space as a society in the 1980s.

At the time, New Westminster built this strange little auto-oriented suburb in the gap between two dense urban community centres. Since the primary built form was “house with a garage facing the street and a private yard in the back” (note this is a generally unusual built form in New West!), the streets were designed with the same exact mindset – they will be used to move cars between garages, and not much else.

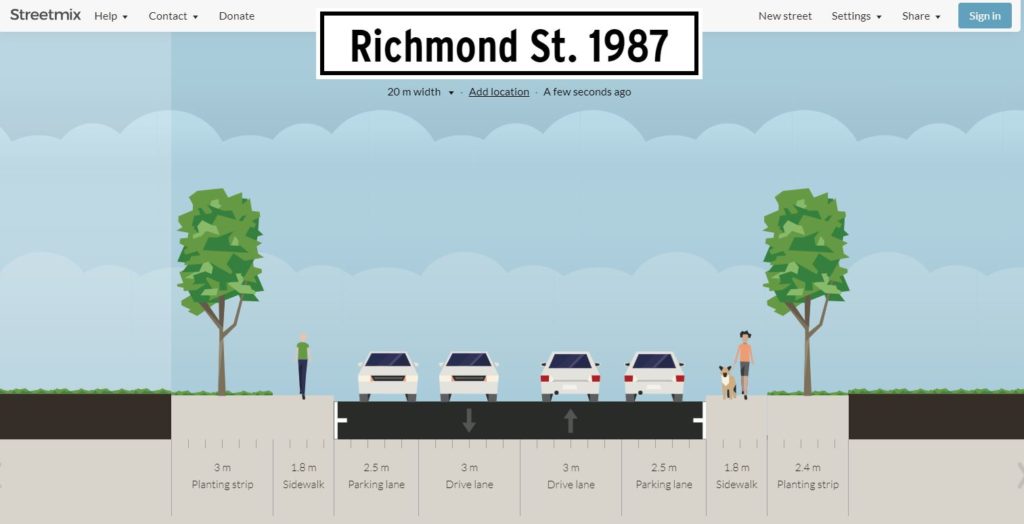

This resulted in some road design ideas that were the opposite of current thinking. Instead of straight lines and a dense grid to connect pedestrians, we build a meandering “arterial” road connecting capillaries of culs-de-sac. Of course these are ostensibly “family neighbourhoods”, so we kept the speed down to 50km/h by putting up a sign, and left plenty of road space for road-side parking and car passage. The curvy hill part of Richmond has wide 20m right-of-way between property lines, but the road profile part (travel lanes and sidewalk) are a pretty typical 14.5m. This feels wider partly because the sidewalks are less than the 1.8-2m wide we would shoot for in 2019, there is no buffer space between the sidewalk and the road, and the parking spots along the road are unmarked and not very heavily used. Add this up, and you have no visual “friction” giving drivers cues to slow down. Wide roads tell people to drive fast, it is human nature.

This is how the road was built in the late 1980s:

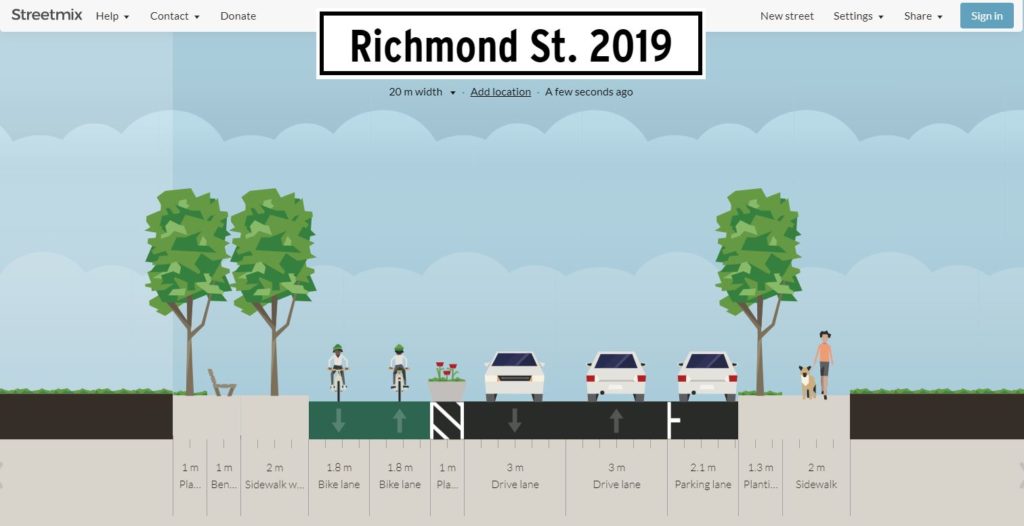

I like to think if we were building the road today, it would more like this:

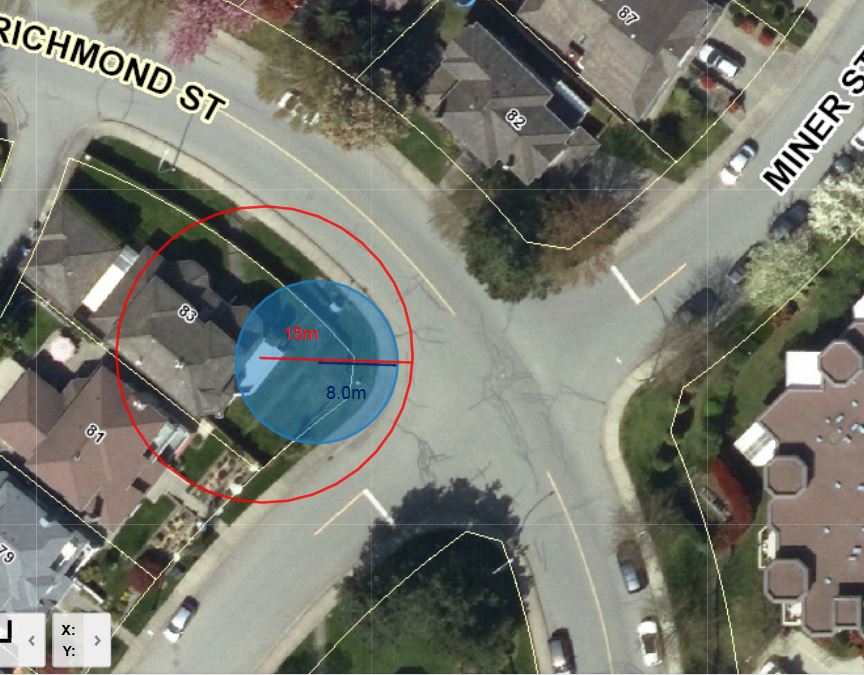

But that is just a representative cross section. There is another issue that makes the pedestrian experience even more uncomfortable. If you look at the intersection of Richmond and Miner, where staff were asked to evaluate placing a crosswalk, you see the corners are rounded off to facilitate higher turning speeds:

But that is just a representative cross section. There is another issue that makes the pedestrian experience even more uncomfortable. If you look at the intersection of Richmond and Miner, where staff were asked to evaluate placing a crosswalk, you see the corners are rounded off to facilitate higher turning speeds:

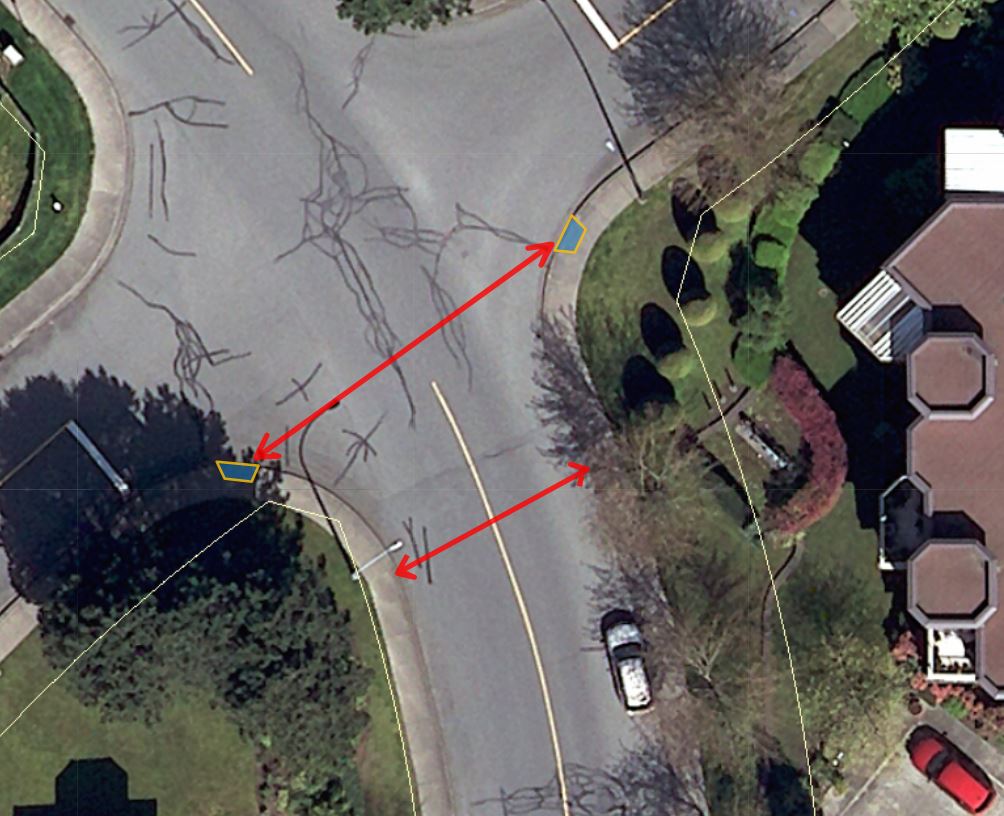

The technical term for this shape is “Corner Radius”. In this diagram you can see the curb follows a curve with a radius (blue) of about 8m, and the effective turning radius (tracing the track a vehicle would actually use for a right turn) is closer to 15m. By modern standards, this is a crazy wide corner, more suited for a race track than an urban area. Reading up on modern urban streets standards, curb radii smaller than 1m are not uncommon, and radii bigger than 5m (15 feet) fall under the category of “should be avoided”.

The technical term for this shape is “Corner Radius”. In this diagram you can see the curb follows a curve with a radius (blue) of about 8m, and the effective turning radius (tracing the track a vehicle would actually use for a right turn) is closer to 15m. By modern standards, this is a crazy wide corner, more suited for a race track than an urban area. Reading up on modern urban streets standards, curb radii smaller than 1m are not uncommon, and radii bigger than 5m (15 feet) fall under the category of “should be avoided”.

The impact of such a wide radius is bigger than just facilitating faster turns, it also creates a variety of sightline problems. See how far back the stop line is on this corner? How far around the corner can a driver practically see? This results in the confusing stop, creep forward, peek, make aggressive move intersection action that opens up opportunity for driver error. This is made worse when there is no clear demarcation of where the parking zone ends near the intersection. Our Street and Parking Bylaw says you can’t park within 6m of the nearest edge of an intersecting sidewalk or crosswalk, but it is less clear where that 6m buffer is when the sidewalk geometry is like this. moving the stop line further forward creates a conflict with pedestrians trying to cross the street at a rational place – where the curbs are closer.

For pedestrians, these big radius corners increase the crossing distances, expanding the time that someone (especially a young child or senior citizen, who travel slower) is exposed to traffic. Crossing Richmond Street at this intersection, the distance between curb cuts is almost 20m, where the sidewalks are only 11m apart a few meters outside of the intersection:

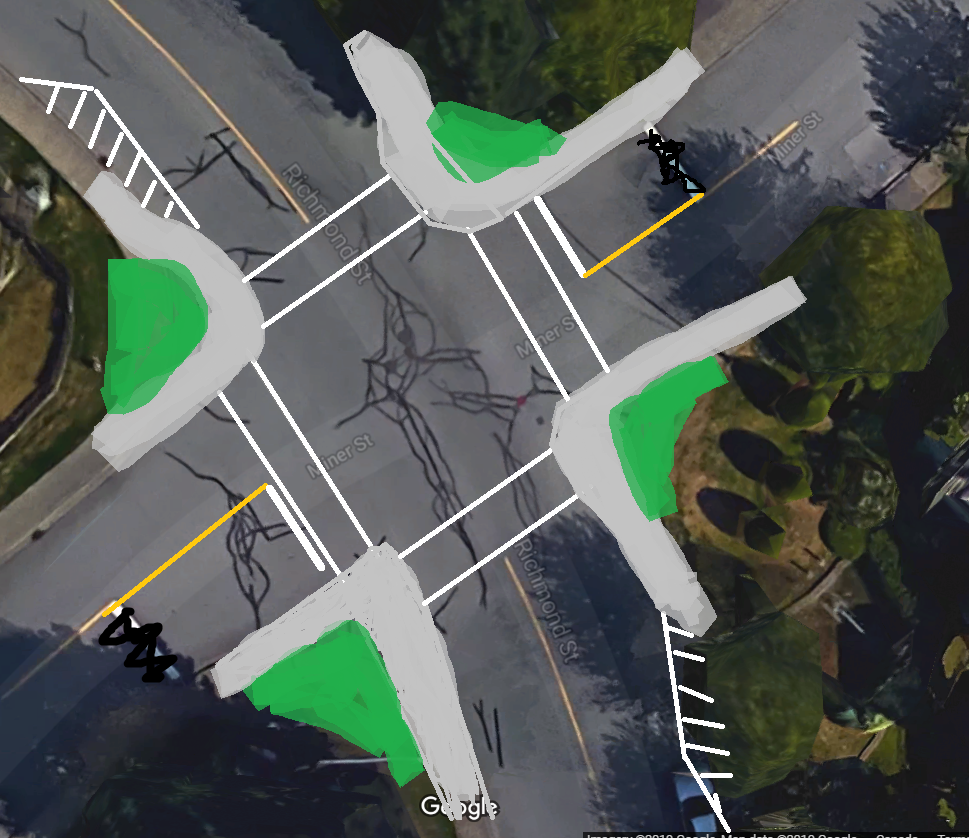

So what do we do? There are lots of useful guides like these great NATCO manuals that show how an intersection like this can be made safer for pedestrians. We can narrow the road at the intersection, paint new crosswalks, and reduce the turning radius through curb bulges:

But my bad painting skills here represent couple of hundred thousand dollars in concrete, road paint, asphalt, curbs, soil, planting and storm drain realignment (never mind a complete re-design of Richmond Street to pull it into the 2000s as I showed in the cross sections above; that would cost millions). And this is one intersection in a City with more than 1,000 intersections, some better designed than others, some more used than others, some with worse safety records than others. I want to change this specific intersection tomorrow, but who is going to come to Council and ask us to raise property taxes by 0.3% to do it? And why do it here and not at the intersection that bugs you in front of your house?

All this to say that some changes are going to be made to Richmond to improve pedestrian safety, and three other intersections (8th Street at 3rd Avenue, 12th Street at Queens, 6th Avenue at 11th Street) that have been prioritized for this year’s Pedestrian Crossing Improvement program, totaling about $200,000 in work. The work is, necessarily, incremental, and because of that it is never enough, and never fast enough.

Be safe out there folks.

There is an interesting approach to improve the intersections without pouring in a lot of money in Calgary: http://www.calgary.ca/Transportation/Roads/Pages/Traffic/Traffic-safety-programs/Temporary-Traffic-Calming-Curbs.aspx

https://www.calgary.ca/Transportation/Roads/PublishingImages/temporary-traffic-calming-curbs.jpg

That’s a great explanation of the design and how our goals have changed over the years. It’s a shame it costs so enormously much to change these seemingly fairly simple things.