When I see voices being raised here in New Westminster and across North America to call attention to inequity society, most prominently the unjust policing of Black and Indigenous people, I struggle to find the place where my words are important. For the most part, they aren’t. As I have spent my life being a tacit beneficiary of this injustice, my lived experience is not something anyone needs to hear from right now. There are better voices to listen to now on this topic. For now, my admittedly inadequate response is to say I am listening, and I am having conversations with people in the community to better understand what kind of concrete actions I can take in my elected role or support others doing to start addressing the systemic change we need to see. I appreciate the correspondence (even the form letters!) I have received, and am struggling to be timely in my replies, but I’m working on it.

I have often tried to use this blog to unpack arcane bits of municipal government. Maybe my usefulness here is in outlining the lay of the land. Not as call for action, an excuse for a lack of action, or a retort against calls for radical change, but more to inform and empower those who would want to call on government to take concrete actions, and those who have concerns about those calls. I think data can help ideas find better traction in local government, in provincial government, and in police forces. So the following is intentionally short on opinion, but I hope this provides local context to the conversations happening across North America right now.

New Westminster has a Municipal police force. Where many communities in British Columbia contract out local policing to the RCMP, here in New Westminster the police are independent. The legislation that empowers them to act as a law enforcement body is the provincial Police Act, which requires that a Municipality provide policing, whether through a stand-alone police force or contracting the RCMP. It also requires that a non-RCMP municipality establishes a Police Board to oversee that policing.

The New Westminster Police Board is (as regulated by the Police Act) chaired by the Mayor of the City, and one of the positions on the Police board can be appointed by the City Council (city councilors are strictly forbidden from serving on the Police Board). The five other members of the Board are appointed by the provincial government via the Solicitor General’s office. So there is a little bit of overlap of jurisdictions, but it is clear the Police do not answer to City Council, for good separation-of-powers reasons. The Police Board oversees (but doesn’t direct) operations, provides guidance on strategic planning, and even hires the Chief constable. These Board members are, notably, unpaid volunteers, and tenure is limited to two three-year terms.

In requiring a municipal government to provide policing, the Police Act requires that a City Council approve a policing budget. Without digging too deep into the current rhetoric, only the provincial government (through the Police Act) or the Police Board can reform the police; while only the City Council can defund them*. Of course, more complicated responses to the complex issues raised by the current public discourse would rely on some sort of concerted action between all three bodies. In short, the systems are structured such that fundamental changes to the status quo will be hard to make, and it is challenging to think about where to start. But that is the challenge before us.

*within certain limits. See my follow-up blog post.

I do want to talk about funding – because the part that is (mostly) under City Council control, and it is something that has become fodder for much of the recent discussion about policing in local government circles.

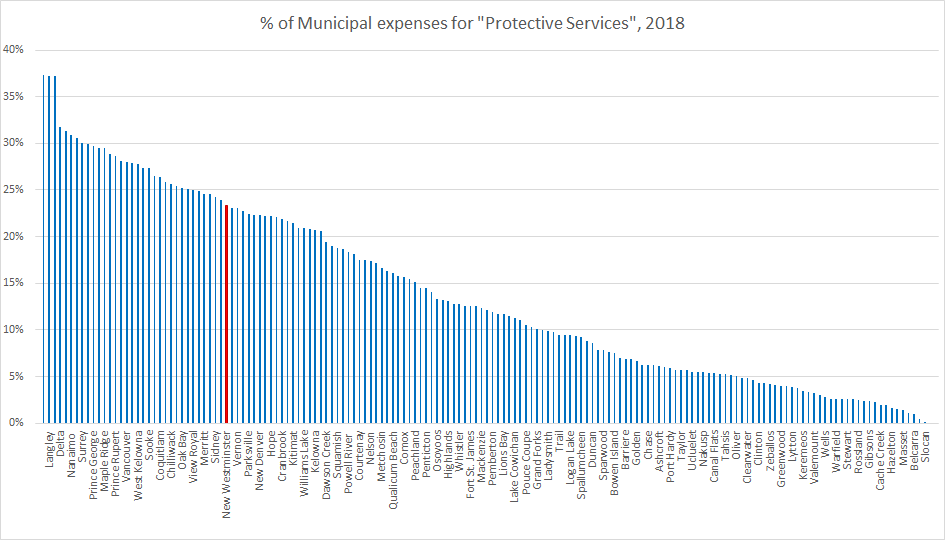

The intrepid CBC Local Government reporter and data geek Justin McElroy put some data together here comparing “protective services” spending across BC municipalities. As he notes, comparing across municipalities is difficult because not all are as transparent about how their spending is broken down. The one definitive source is the BC Government stats collected annually, but they report “protective services” as one category which lumps together Police and Fire. Looking at the 2018 data (the most recent available on-line), on average 25% of local government spending is on Protective Services. New Westminster is a little lower than that average at 23%.

This proportion varies widely across the province for many reasons. Victoria has high protective service costs at least partly because it is a small municipality in the middle of a large metro area with some special policing costs related to being the Provincial Capital. Salmo has a small volunteer fire department and limited policing provided by the RCMP, so their protective services costs are really low. There are also great variations on the denominator side of the equation, as different Municipalities have different utility costs and other levels of service in non-protective services. So, all that to say direct comparisons are complicated.

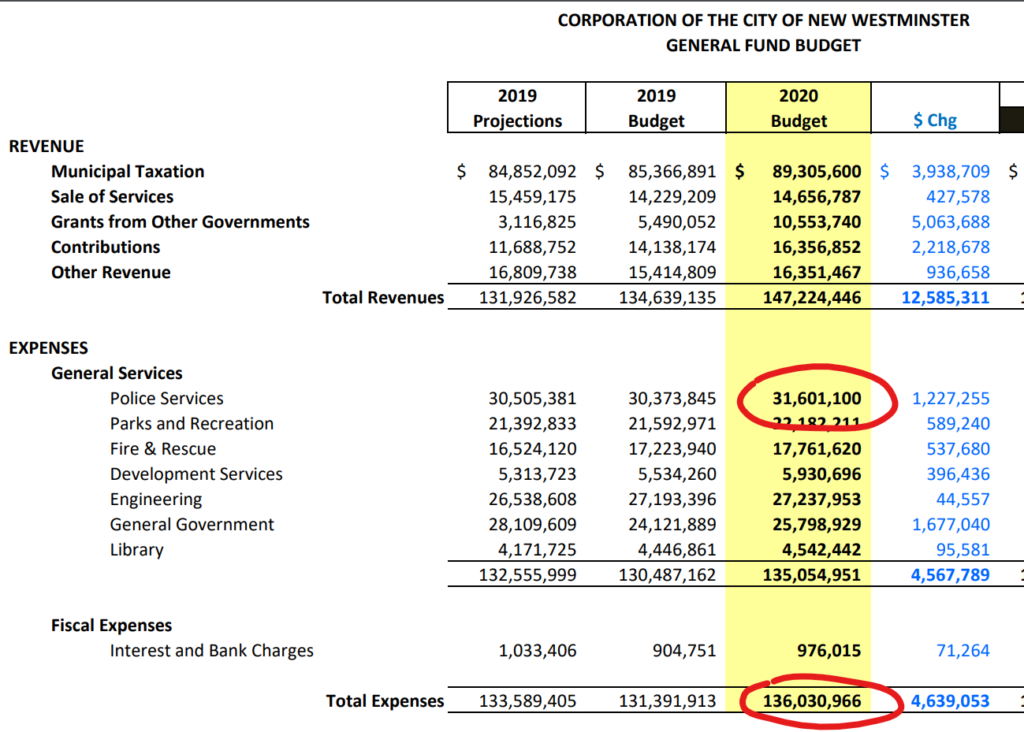

I can talk with a little more certainty about New Westminster’s spending on police services. If you look at our most recent on-line financial reporting here, you can check the 2020 Budget column to see what we plan to spend this fiscal year:

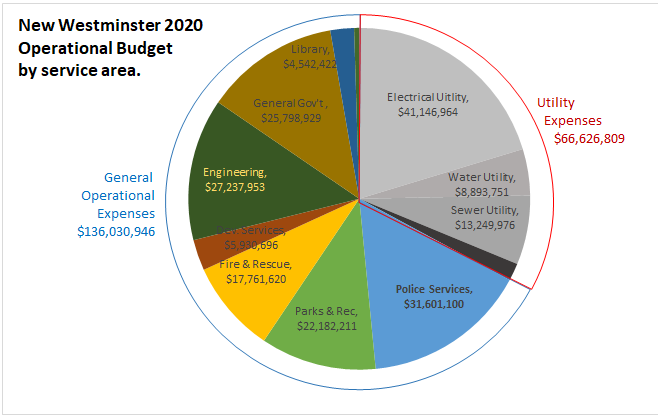

This is cut from page 19 of the pdf in the link above. This is the “Operational” part of the budget, which pays for day-to-day expenses like salaries, gas for police cars, electricity and paper clips. Utilities like sewers and electric are handled separately in the same report because the sources of those funds are different. In 2020 the City budgets to spend $136M on non-utility operations, and $31.6M of that is police operations. It is fair and accurate to say that 23% of our non-utility operational spending in the 2020 budget is on Police operations.

There is a second budget category the City uses to account for its “Capital” expenses. This covers all of the tangible objects the City has to buy that have a useful life span (i.e. are not consumables) but need maintenance or periodic replacement, like buildings, cars, roads, ice plants for arenas and lawnmowers. On pages 25 and 26 of that linked pdf above are the details of what we plan for Capital spending for the 5 years covering 2020-2024. It totals up to a substantial $275M, but if you take all the lines that are for Police services, you see $427,600 for police building repairs & renovations, $828,600 on general equipment and $2,085,000 on police vehicle renewal and repair for a total of $3.3M, which totaled up works out to a little more than 1% of our 5-year capital budget. Savings on equipment is relatively easy, but that is a small proportion of the city budget.

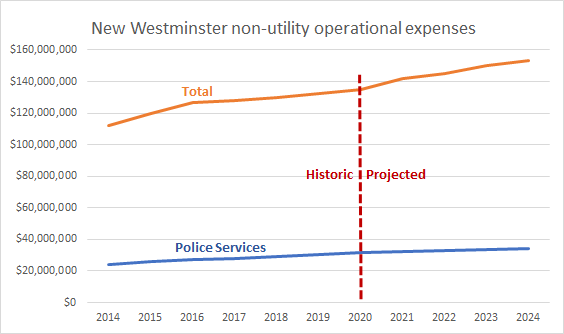

Finally, it is timely to discuss how the local police services budget has changed in the City. The City doesn’t archive old financial plans on the website, and the Provincial stats lump all “protective services” together. However, I do have copies of all of the annual budgets I have been asked to approve since I joined City Council in 2014, and can project forward to 2024 using the current 5-year financial plan (which are projections that may change). Here is what the Police Services portion of the general operations budget looks like over that time. It has remained around 22%-23% of the budget over that time, but is increasing at a slightly higher rate than overall budget:

We can talk about reasons why the police budget has changed over the years, and yes I have opinions, but maybe I’ll leave that for future discussions I am sure we will be having.