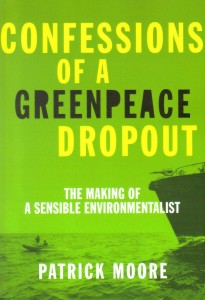

Sorry to be so slow, but life is really busy right now. We are in the middle of an election campaign, there were some family emergencies, and work has been crazy busy. On top of my evening blogging schedule, I haven’t had a lot of free time to read. Oh, to be bored for a change!

Once we got past some of the painful introductory materials, the book gains some steam as Dr. Moore outlines his storied career as a Greenpeace organizer and campaigner. The short versions is that these guys were “Type-A” with a seemingly complete lack of common sense. They thought nothing of buying an old fish boat, spending a few weeks (or months) patching the holes and getting the motor running, and sailing out in the Pacific Ocean! They dodged weather and ran directly towards trouble with the US Coast Guard, the Soviet Union, the French Navy, and Japanese whaling ships. The rented helicopters and, with a paucity of planning, flew out onto ice floes in the Atlantic to film seal hunters.

At the time, they created in Greenpeace a heroic mythos though very careful collection and distribution of pictures and film. Dr. Moore outlines how co-founder Bob Hunter developed the idea of the “Mindbomb” – that perfect combination of images and words that the media (and the media consumer) could not resist putting on the front page – a phenomenon the New Media calls “going viral”.

In essence, Greenpeace did not sail to Amchitka to stop a nuclear test, they went there to create a Mindbomb that would shift the public conversation so that more people took the idea of banning nuclear testing seriously. They didn’t race around the Russian Whaling Fleet in zodiacs to save any actual whales (in fact their efforts were clearly fruitless), they did it to create the images of a bunch of heroes racing around in big seas challenging the Great Soviet Fleet to get the pictures in the newspaper and bring light to the plight of the world’s cetaceans. Dr. Moore didn’t sit on a baby seal in Labrador to stop it from getting clubbed, he did it to get photographed being arrested for assaulting a seal, when he was the only thing between that cute little bastard getting clubbed and skinned.

I found one interesting link behind all of the campaigns Dr. Moore took part in during those early days of Greenpeace. None of them are really about environmental sustainability as we think about it today. Besides his first trip to Amchitka to call attention to nuclear testing, all of his campaigns were centred around animal rights.

Although the entire anti-whaling campaign was around protecting several species of whales that had been hunted to the brink of extinction, Dr. Moore does not talk at all about this as a sustainability issue (as we talk about shark finning or the Bluefin Tuna fishery today), he talks about the majesty of the beasts, the intelligence of the animals, and the cruelty of hunting them.

“There is no way to kill a whale in a humane manner. Among the tens of whales we witnessed being harpooned over the years, most died slowly, spouting blood and gasping desperately” [pg. 70]

” With two Zodiacs and a rough sea we tried desperately to shield the whales during the next two hours as they were gunned down one after the other. The crew watched from the deck of the James Bay as blood filled the sea around us, whales screaming and writhing in agony until all was quiet… It was a gruesome scene and ironically it worked very much in our favour.” [pg. 94]

The anti-sealing campaign was more of the same, much about saving these cute fuzzy animals, with no discussion at all about whether the hunt was sustainable, economically important, socially significant. Greenpeace flew in movie stars to create “mind bombs” in the defence of defenceless (and cute) animals. Greenpeace of 1975 is not like SPEC of 2010, it is like PETA of 2011.

Notably, this was all before the Bruntland Report, and therefore before the modern concepts of environmental sustainability had really been developed, so the ideas were not well known outside of rather obscure schools of development and economics. Suggestions of future resource depletion were usually brushed aside by claims of people being too “Malthusian” or not having enough respect for engineering (see discussion of Ehrlich vs. Borlaug in this very book, pp.56-57).

This brings us to 1984 -1986 – the Second Act in Dr. Moore’s story – when he began stepping away from Greenpeace. This was a tumultuous time, with him raising a family, getting a real job, and the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior. But it was also the time that Greenpeace began to campaign for sustainable development in industries that were close to Dr. Moore’s roots and his family. After all, he was the son of a rain forest logger who was setting up one of the first salmon farms on the west coast.

He claims it was the Greenpeace initiative to “Ban Chlorine” that was the final straw, as he thought it wasn’t science based thinking. Problem is, no-one in Greenpeace seems to recall them saying they want to ban all chlorine from the planet. Greenpeace did take a strong stand then (and still do now) on the spilling of organochlorines related to paper bleaching, and the use of toxic chlorine-based substances when non-chlorine-based substitutes are available. That has extended to the modern practice of using PVC in places where environmentally-less damaging alternatives are practical. Considering how much of my time I spend at my work dealing with contaminated sites featuring hard-to manage carcinogenic, mutagenic and acutely toxic chlorinated solvents organochlorines, I don’t think it is unreasonable to ask questions about whether the money we save over using the less toxic alternatives is really money saved at all.

Or maybe Greenpeace was just using the idea of “banning chlorine” as a “Mindbomb” to get a few headlines and point the media to the real issues of chlorine in our environment. “Ban Chlorine” and “Devil Element” are much more compelling than “Organochlorides in our environment increase cancers and impact marine wildlife”. It is telling that Dr. Moore’s biggest conflict when he left Greenpeace is the guy who invented the “Mindbomb”. Dr. Moore himself admits there was no way he could save the seal pup he sat on, but he wanted to be filmed losing that fight – Mindbombs were rarely science-based.

It seems the nuance of this argument is lost to Dr. Moore, as he again dismissively waves away any concerns about the chlorine industry or the hazards of organochlorines by creating this long-winded false dichotomy argument and telling us that chlorine is the 11th most abundant element on Earth and table salt is 2/3rds chlorine, so how can that be bad?

On page 142 he goes off on a diatribe about the wonders of chlorine that includes a huge strawman argument (“[long list of potentially toxic metals]…all have important uses in health, technology, energy production and lighting”); a non-sequitor (“we have been bombarded into thinking lead is deadly, yet many of us drive around with 30 pounds of it in the battery of our cars.”); rank hyperbole (“chlorine is the most important element for public health”); the naturalistic fallacy (“Even herbal medicine is partly based on using plants that contain chemicals that are toxic”); and a long false dichotomy I won’t bore you with here. He even decries that although he was the lone scientist in the discussion, none of the other Greenpeace crew respected his scientific prowess. He follows this by describing Renate Kroesa (who, being a chemist, would qualify as a scientist to most of us) as “fanatical”. Page 142 is one of those pages of this book that I have marginal-marked the hell out of in red ink. It is just a bad argument, poorly supported, and it leads us into the wonders of his approach to fish farming, but I will blog about that in a later post.

Dr. Moore says he is proud of his work at Greenpeace, proud enough to engage in a bit of hyperbole:

“We got many things right in the early years of the movement: We stopped the Bomb, saved the whales, and ended toxic discharge into water and air.” [Pg.141]

Um, last time I checked we still have nuclear weapons and nuclear proliferation is an increasing risk in the world; whales still face serious threats from habitat loss and pollution, and are still being actively hunted by several nations; and toxic discharges in to the air and water seem to continue world wide.

However, I am not going to take away from Dr. Moore the achievements of Greenpeace during his time there. He took a rag-tag groups of hippies on a fishboat and spun it into a multi-million dollar international organization that spoke truth to power on many fronts, often powered by little more than a string and a prayer. From reading his accounts of those early years, there were more than enough internal and external forces that could have torn it apart, and too many strong personalities and personal agendas (Paul Watson, anyone?). It should not have lasted, but pretty much everything we know in 2011 about the environmental movement, the good parts and the bad, can be traced back to the early efforts of Dr. Moore and Greenpeace.

Without him, I imagine this blog would have a different name!