Someone asked—

Hi Pat,

My partner and I live in Queensborough. We are both plant lovers and native plant specialists, and have come to love our little place by the river – such a magical mix of water, plants, and living things… We often take walks along the waterfront and up and down the tattered side roads with their open ditches filled with teeming plant and animal life. We are constantly enjoying the native plant life that has been cultivated and also occurs natively in the area, but have a number of concerns.

First and foremost, we recently noticed that in the last month or so, a large number of big trees and shrubs were removed from the riverfront with no notice. This is the side that faces Annicis Island, and I believe a lot of the trees were deciduous. Willows, Mountain Ash, and other trees were chopped down as well as the other herbaceous and woody plants. This is something we notice happening on a small scale along the ditches as well. Most importantly, we’d love to know why these large trees were cut down, most likely because of disease or pests, but absolutely no signage was placed on the path in the Aragon where all the cutting happened, and we are very curious about the city’s policy on controlling these wild areas, if any. Could you send some information our way please in terms of this? We’d also love to know what the plan is for the large biodiversity of plant and animal species that are consistently being eaten up by the growing development and if these open ditches and waterways will somehow remain untouched. We are looking forward to new development, the Q2Q bridge more than anything and additional retail, but it worries us to see so much changing too. We would also like to know what to do when we see ditches and waterways which are being clearly polluted by the nearby industrial?

Thanks so much for fighting for a better city for us all. We look forward to your responses, and finding a way to make Queensborough more of an example of environmental stewardship. There are few places like this left – water, plants, and living things together – that have the potential for so much life and health, and unfortunately there is much work to do still, and remediation to be completed on what was done long ago.

This is going to be one of those good-news bad-news answers, depending on how you feel about ditches/watercourses. I’m likely to go on at length here, as there are actually several questions here, and I’m going to try to hit them all systematically.

I also love the Queensborough waterfront, especially the south and east sides where the City and developers have invested in the restoration of the waterfront, and have effectively made it a comfortable human space and an ecologically productive space. We just had the 4th (5th?) annual shoreline cleanup along South Dike Road, and the impressive recovery of native species and ecology along the river is always inspiring.

The fate of inland ditches in Q’Boro is, however, one of those political hot-button issues, where someone is going to be unsatisfied whatever the City does. For all the people in Q’Boro who love the frogs, the dragonflies, the ducks and even the occasional stickleback, there is at least another who hates the murky water, garbage accumulation, loss of parking, and general untidiness of having an open ditch in their front yard. I’m not going to opine whether you are outnumbered or not, but you are definitely outvolumed by people demanding that the City get rid of the ditches and install “proper” sewers as soon as possible.

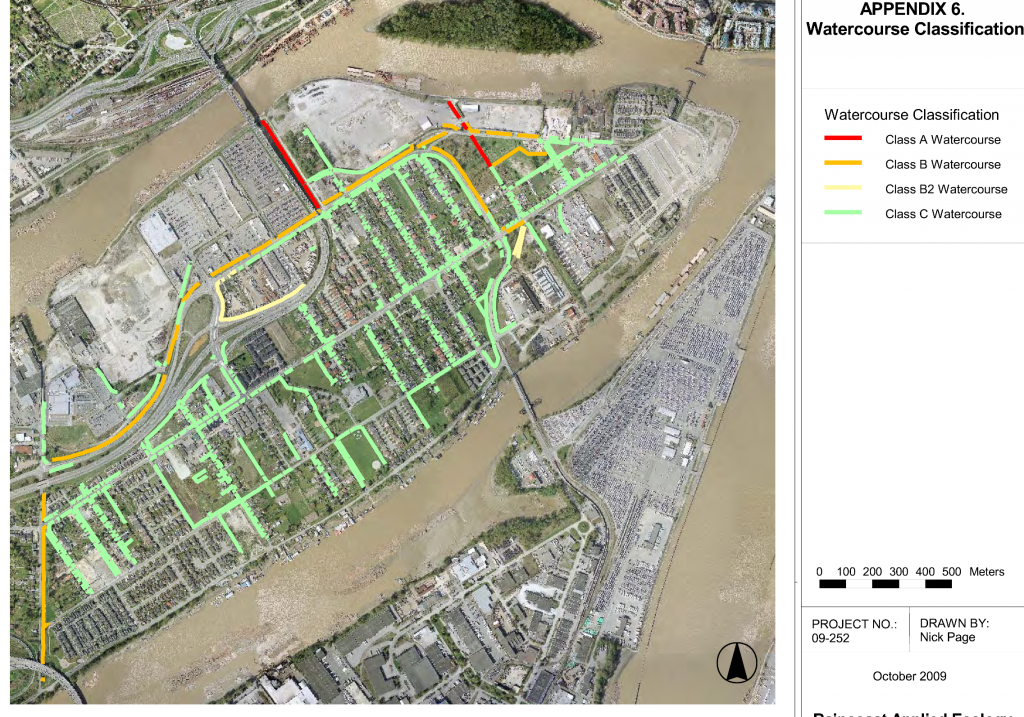

From an ecology point of view, some of the watercourses in Q’Boro are protected by the Riparian Areas Regulation (RAR), a provincial regulation that is, quixotically, managed completely by local governments. Not all “constructed watercourses” are protected, however, as ephemeral and isolated watercourses and those already severely impacted are not determined to have high enough ecological value to receive full protection of their riparian areas. Further, the riparian protection need on some of the larger ones plays second fiddle to the need for maintenance to keep the water flowing and houses from flooding.

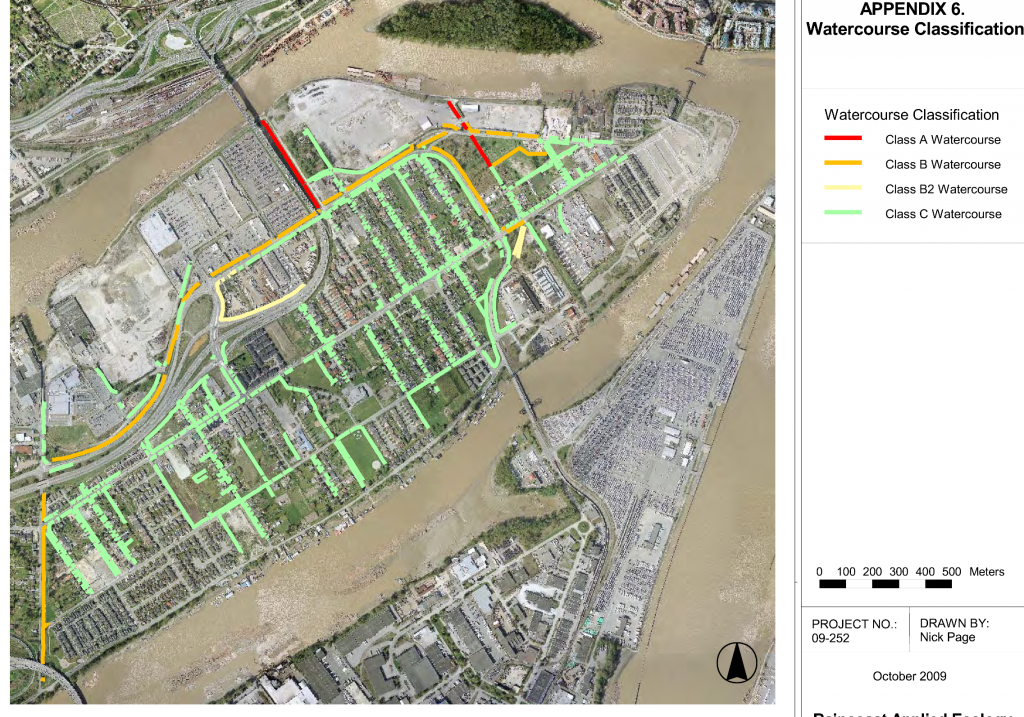

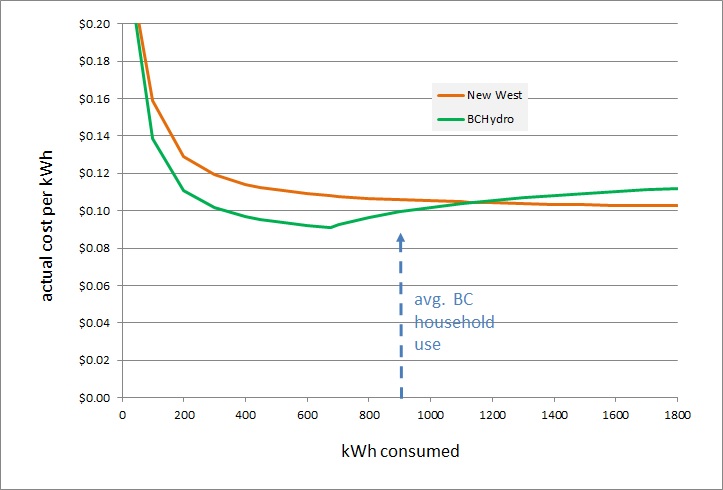

The City performed an ecological mapping exercise back in 2010 that, amongst other things, showed the classifications of the watercourses in Q’Boro. Several of the larger ones (Class A and Class B) are protected, and are not likely to be filled in the long-term. There are provisions on in the RAR for preserving and improving the quality of the habitat around them, including trees and shrubs, which can curtail development and prevent them from being filled. When you balance the need to maintain these watercourses as conveyances with the need to protect the ecology, I wouldn’t say they will remain “untouched”, but more that our engineering folks will try to protect the native species and habitats as best they can while keeping people’s houses dry.

Filling in even the smaller, unprotected ditches creates yet another problem, this one purely engineering. An open watercourse can store and transport a lot more water than if a pipe was dropped into that watercourse and it was covered up. To replace the storm water management and flood protection capacity of all of the open watercourses in Q’Boro would require huge pipe infrastructure, and all of the associated catch basins, inspection chambers, and pump infrastructure. To make matters worse, the soils in Q’boro need just as much engineering and densification to hold up a sewer pipe as they do to hold up a housing complex, which significantly increases the cost. Don’t get me started on the shallow water table and the construction/maintenance problems it causes.

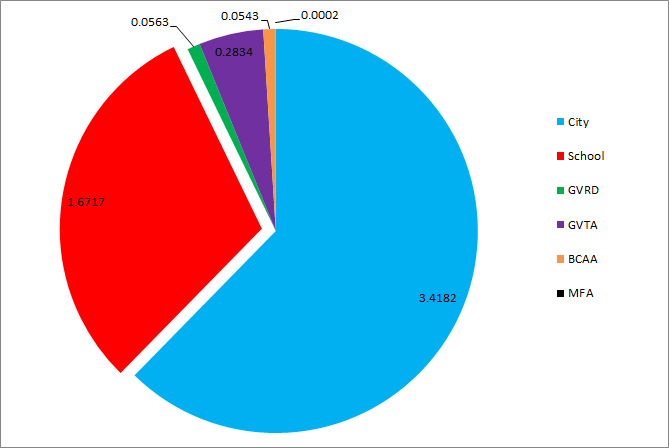

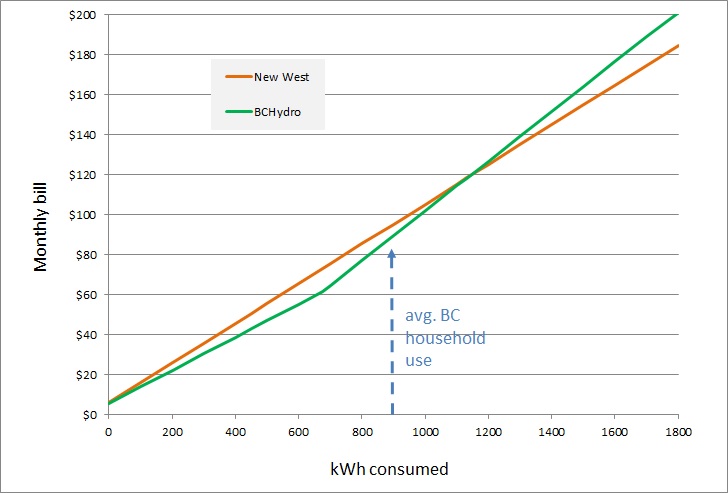

Therefore the City has developed a longer-term strategy to plan for, and pay for, drainage infrastructure improvements whee they are appropriate, and addressing the eventual filling of the smaller, disconnected ditches that are not protected by the RAR. New developments in Q’Boro pay into a special DCC earmarked for drainage improvements, separate from the mainland and dedicated to works in Q’Boro. When a developer builds in Q’Boro, we take advantage of the soil densification and drainage planning they are doing to make it more affordable to install new infrastructure.

Residents in the Single Family House neighbourhoods who wish to have the drainage closed on their block can do it through a “Local Area Service Plan”, where they get the work done in a cost-sharing with the City (and pay for it over time through their taxes), as long as it isn’t a watercourse protected by the Riparian Areas Regulation (i.e. Class C or worse). We received a report to council in September 2014 (see page 88 of this lengthy Council agenda if you are curious).

Now onto the trees. We do have a recently-adopted Tree Protection Bylaw that applies to new development, City lands and private lands. I don’t know the details of the tree removal you are talking about, but if it happened after the Tree Bylaw was adopted (January 13, 2016) and didn’t occur on Port-owned land, then there should have been a posted permit. If the trees were hazardous or dangerous (as determined by a professional Arborist) then they will be replaced on a one-for-one basis. If they were simply removed to facilitate development, they will be replaced on a two-for-one basis. It isn’t perfect (two young trees don’t necessarily provide the ecological benefit of one mature tree), but it balances the limits of power a local government can do when approving development on treed lots with our desire to have more trees in our community. When planning for trees, one must have a 20+ year vision.

What to do when you see industrial pollution in ditches? First off, you need to know if it is really “pollution”. The groundwater in Q’Boro is similar to adjacent Richmond, in that it is a product of being a former peat bog. The lack of gradient and boggy soils result in stagnant groundwater that, for a bunch of biochemistry and geochemistry reasons I won’t get into here (did I mention I’m an Environmental Geoscientist working in soil and groundwater protection?) has very low dissolved oxygen, low pH and lots of dissolved metals like iron and manganese. When that groundwater hits our ditches, it is exposed to atmospheric oxygen, causing those metals to precipitate out in to metal oxides (making it murky and rust-coloured), and in the presence of biology, more complex metalliferous organic compounds. What sometimes looks like and oil slick in the water may actually be a natural “metalliferous sheen”

That said, all the ditches in Q’Boro connect directly to the Fraser River without any kind of water treatment, so real polluting substances going into the ditches will more than likely find their way into the river. Section 36 of the federal Fisheries Act says you can’t do that, and enforcement of that law falls on Environment Canada. However, response to smaller spills in to fish habitat is a multi-level cooperative effort between EC, the provincial Ministry of Environment, the Coast Guard (if it hits the river) and local governments. In that sense, who you should call first probably depends on the situation.

If you see something curious, but you are not too sure, either use SeeClickFix or contact the City’s Engineering folks, and they will check it out.

If you see what is clearly a spill, and are worried about fish or see potential impacts to ducks or any such concern for wildlife, you should contact the provincial spill reporting phone / app, and they will triage and determine the proper level of response and response agencies.

If you see a dangerous spill, such as an overturned gasoline truck or a dump of dangerous substances where there may be human health or property damage implications, you should call 911 and ask for the fire department. They will be able to determine a safe response strategy, can arrange for evacuations or road closures, and can coordinate with the City’s engineering folks and senior governments whose job it is to stop the spread and coordinate the clean-up in a way that keeps people from getting hurt.

Finally, what can you do to see more ecological protection of Queensborough, and New Westminster in general? You might want to make contact with the New Westminster Environmental Partners. They organize the Q’Boro Shoreline Cleanup every year, and are always looking for interested and knowledgeable people to help with environmental protection advocacy and works. You can also consider joining the City’s Environment Advisory Committee, which advises Council on topics environmental. The application period for 2017 is open right now, and we don’t generally get a lot of applications from Q’Boro for City Committees. Bringing your voice to the table may help the City make better decisions regarding ecological protection of your neighbourhood.

Whoo Hoo! Two ASK PATs in a row that end with plugs for joining City Advisory Committees! People should really apply!