Happy Family Day Weekend. It gave be a chance to catch some breathe and look at my Ask Pat queue. The first one I found is pretty long, so I edited it back a bit and will break it into three parts:

FossilFool asks—

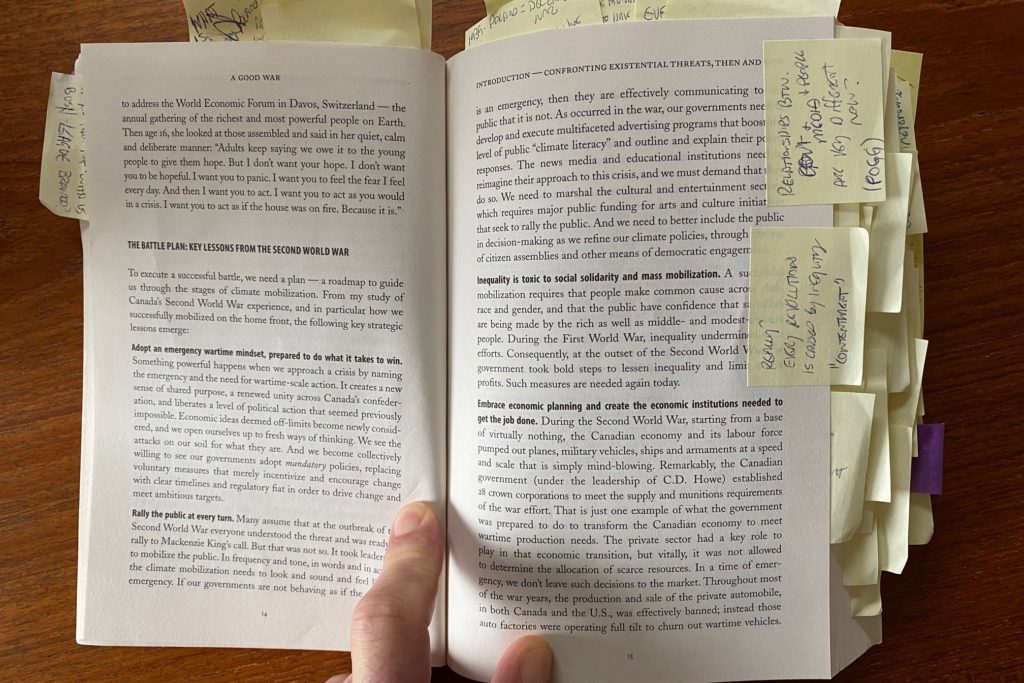

Hi Pat, I’ve been inspired and challenged lately by the book, A Good War, by Seth Klein, about how we can look to how Canada responded to WWII as an example of how we could mobilize the country to respond to the climate emergency like an actual emergency.

Not a question yet, but let me interject to say: Me too! I have not only read it, I have marked up, flagged, and taken extensive notes about it:

I did this because I had the challenging job of interviewing Klein as part of the 2021 Lower Mainland LGA conference. The book is incredibly well researched, and so full of both historical facts and compelling ideas that engaging the author in a conversation about it is a bit intimidating to a lowly Earth Scientist. But it definitely tells a different story that we usually read about WW2. Not of the soldiers that put on uniforms, but of the leaders in government and in industry that saw an existential threat and – in less than a year – completely restructured the Canadian economy to address that threat. Perhaps as amazing (and I’d suggest a better comparable to the Climate Emergency as we come out of a global pandemic) how once the threat was abated, the country immediately and completely restructured its economy once again to stop making so many weapons, and to instead assure people had education, jobs, homes and pensions in the post-year period.

The historical record is amazing, and Klein does a good job drawing parallels (and addressing contrasts) to the current existential threat, and does not leave the question of why we are unable to respond as we did then unexplored. Perhaps surprisingly non-partisan and clear on the positive role capitalism can play in driving change (though he spares little empathy for neo-Liberalism), he nonetheless makes a clear case that it is only bold leadership that is missing. It’s a good read, and a good message.

It seems clear that we need to get off of fossil fuels FAST to really make any significant impact in slowing/limiting climate change. The City of Vancouver has some ambitious goals to get homes to switch entirely away from natural gas, and I’m wondering if other municipalities like New West will soon follow?

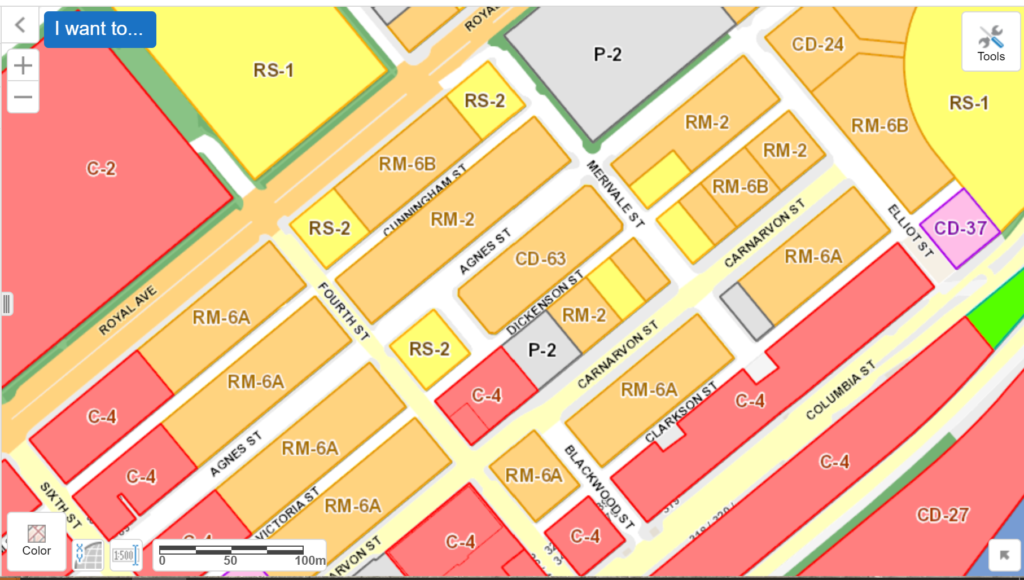

Some municipalities like New West are signaling that goal (see Bold Step 3: Carbon Free Homes and Buildings), but Vancouver is in a unique situation, which is why this is an area they are able to take real leadership. Because of their unique enabling legislation, the Vancouver Charter, that City has the ability to regulate its own building code. That means they have the authority to say “we will not permit gas appliances in new builds”. New West and other Municipalities do not have that power. We would need the province to grant us this ability.

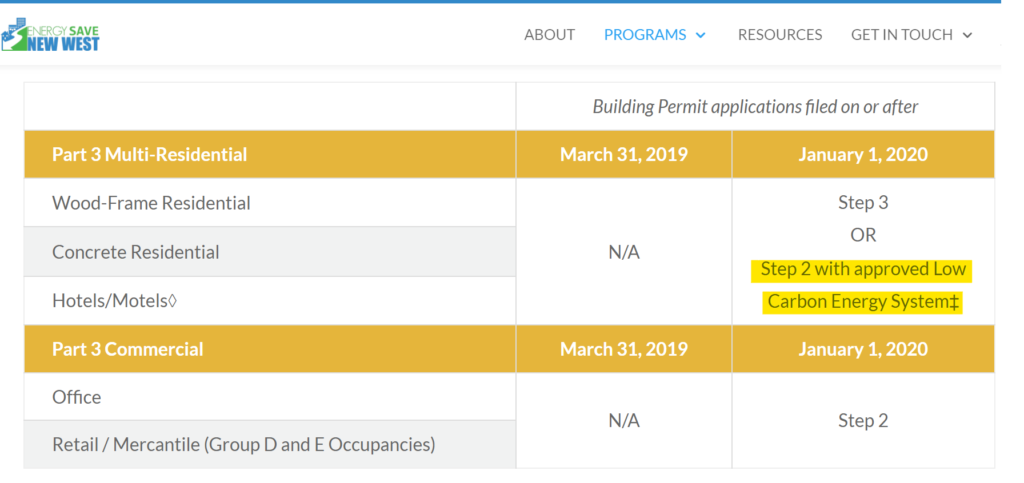

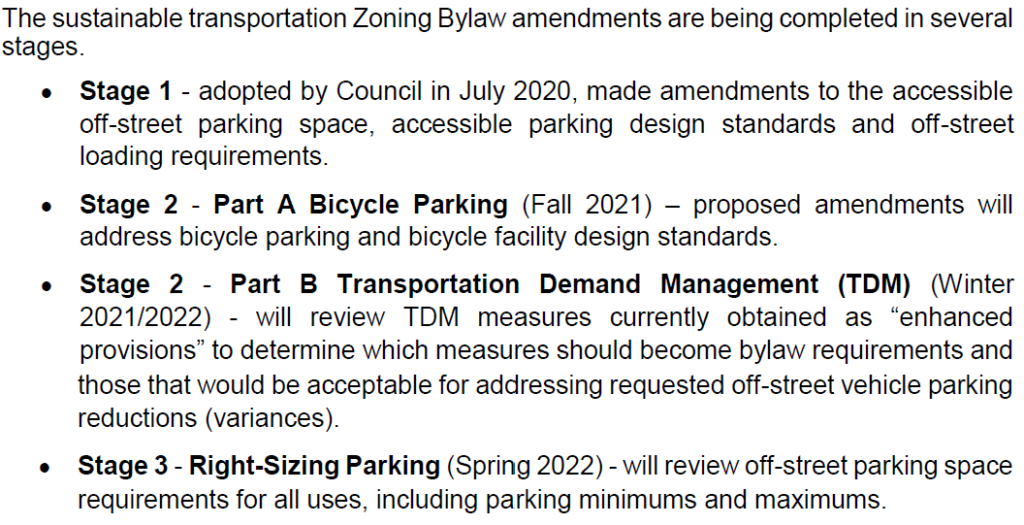

Lacking this stick, we still have access to some carrots. This means local government programs to coordinate or add to senior government and industry incentives to switch to electricity. We can also use the greater flexibility in the Step Code to incent change to carbon-free energy. The Step Code is a provincial energy efficiency standard applied to new buildings. Local Governments have the authority to choose which “step” new buildings have to meet, each higher step meaning higher efficiency of the building, but also meaning higher building cost and possibly other compromises in the design of the building. A creative use of the Step Code would allow builders to build a less efficient building (therefore saving money) if they choose only non-carbon appliances for the building. The resultant building may use a bit more energy over its lifetime, but with New West’s electricity effectively zero-carbon, this might be a good bridge to accelerate the transition off fossil gas. This is the path New West is following, starting with “Part 3” buildings, and (knock on wood) coming to other building types soon:

I checked out the EnergySave New West page and can see that there are a bunch of rebates being offered for energy efficiency upgrades, but I was surprised to see that many of them are actually incentivizing changes that still rely on natural gas. If we need to get off of burning fossil fuels period to address climate change, why are we still talking about energy efficiency upgrades that don’t actually achieve that? I’d love to get your thoughts on this. Thanks for your time and for your great blog!

Yes, there are still incentives for people who want to get more efficient gas appliances such as modern furnaces and instant-water heaters to replace hot water tanks. Energy Save New West points people at incentives offered by the City and those offered by the Province, BC Hydro, and Fortis. Though the City does not specifically incentivize gas appliances, we do point people to incentives that exist to encourage them to install more efficient gas appliances.

The debate about whether “more efficient fossil gas appliance” is an appropriate idea right now in light of the climate emergency is definitely a live debate. I know where Seth Klein would fall on this, and I might lean that direction myself. But there are specific and financial barriers to some people going full electric right now, and the gap is not filled by available incentives. For someone with a gas instant water heater and gas stove, switching to electric may require significant upgrades to the electrical system in the house to accommodate the high amperage demands of those appliance types, and a new line and transformer connection for the house at a cost much higher than the appliances themselves. Providing incentive to reduce overall gas use still pays GHD reduction dividends, but I hear you about the incrementalism.

We need to get off fossil gas, and I’m afraid programs like 30by30 are at best stop-gaps until we get to that point, at worst speedbumps slowing that transition. Through my work as the Chair of the Community Energy Association, I have seen first hand how Fortis (who is one of our members) has tried to define and redefine what its role is in this seemingly inevitable transition. They are indeed pushing the envelope on the efficiency of gas for buildings, including a pretty remarkable Deep Energy Retrofit program with serious resources behind it. But I sense a more fundamental shift in their business model is going to be needed if they want to prosper through this time.

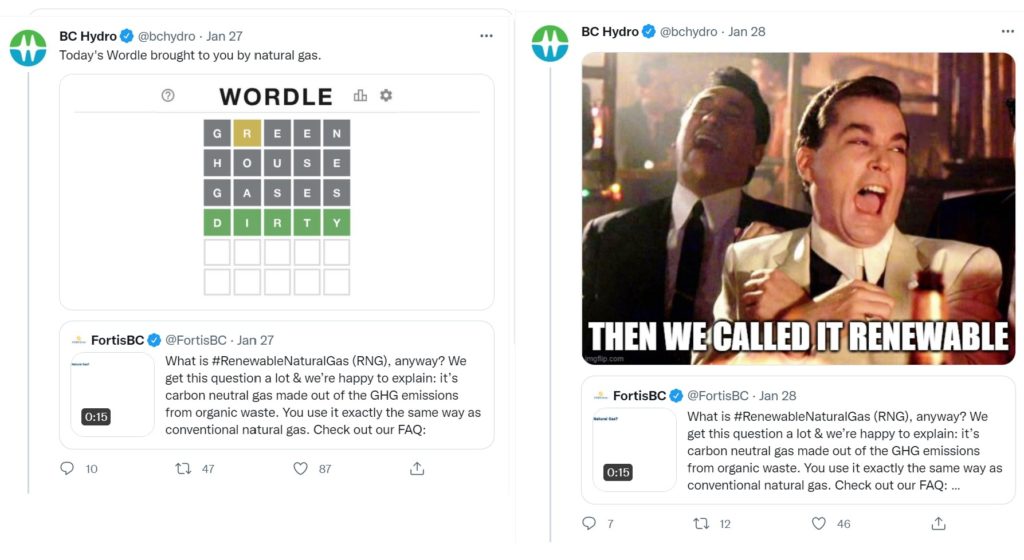

That said, I have also noted how BC Hydro has adopted a bit of a cheeky attitude when discussing the need to transition from gas to electricity:

As we have all learned by now, by the time any public debate gets to the TwitterSnark stage, the solutions will soon be in hand. Right?

M

M