The long-anticipated and irrationally-political Mobi bikeshare program has finally launched in Vancouver. I hope it works, but have my doubts.

Regular readers (hi Mom!) will remember that I went to New York City around Christmas time last year, and had a chance to try out their massively successful bikeshare program, product-placemently named “Citi Bikes”. The experience not only made me a fan of bikeshare- but changed a lot of my misconceptions about what bikeshare is. As I see many of my own misconceptions being repeated in the Vancouver media (social and otherwise) around Mobi, it is worth discussion.

Citi Bikes operate on short-term rental system. You can pick up a bike while walking by a station, and ride for up to 30 minutes (or 45 minutes if you have an annual pass) before you need to check the bike in again at any station. You can buy a day pass for $12, which gives you unlimited rides within 24 hours, or you can buy an annual pass for $150 and use it whenever you feel the need.

Now, 30 minutes seems a pretty short period of time to rent a bike, but that is the entire point of the system. If you want to rent a bike for a couple of hours to noodle around Stanley Park, or for a few days to add biking adventures to your vacation, then a private bike rental company is still the best option for you. Bikeshare is not about replacing other bikes, it is about expanding your walking distance and facilitating multi-modal trips.

I can probably explain better by talking about the day we spent in Brooklyn and Manhattan using Citi Bikes:

- We walk the block from our place in residential Bedford-Sty to our nearest Citi Bike Station. After about 5 minutes of paying for a day pass and checking the bikes out, we were on our way east along brownstone-lined streets.

- About 20 minutes later, we were at Barclay’s Centre where another Citi Bike station was awaiting. We dock the bikes and hang out a bit at the sprawling plaza. The dock also has a digital map kiosk, so we orient ourselves and plan the best route to the Brooklyn Bridge before we check out a couple of new bikes.

- Near the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, we dock the bikes. We grab a coffee, then wander over to the bridge. The pedestrian/bike walkway is packed with tourists, so we slowly walk across enjoying the sites, the crowd, the experience, without abandoning bikes at one end we need to retrieve later, or feeling like we needed to drag them along.

- We spend an hour or two wandering around China Town and Little Italy, then hop on a Citi Bike to loop around the Bowery to the Village. Some places were better for walking, some better for riding, and we made the choice.

- After some more meandering, we check out another set of bikes and cross the Williamsburg Bridge. Back on the Brooklyn side, we quickly swap bikes to get ourselves an extra few minutes, then head through Williamsburg to find a brewery.

- After a tasting and a meal and some wandering about loving the vibe of Williamsburg, we found a nearby station and mapped out the best route home to Bed Sty as the sun was setting. Probably being a 40-minute ride at an easy pace, we figured we would need to swap out bikes half way. We didn’t know about the “Citi Bike Dead Zone” in the Hasidic part of south Williamsburg, but managed to find a station with 5 minutes to spare. If we had downloaded the Citi Bike App, we could have avoided this peril.

- Back at our base station as it was getting dark (the Citi Bike has built-in front and rear lights run by a generator in the front hub), we checked in and walked the block home with time enough to catch a great Sousaphone-Accordion trio.

A nice 8-hour day, about 7 bike station stops, we probably covered 20 kilometres on bikes, just to connect up our fun walking spots. We never fussed with a bike lock (or a helmet – more on that later) or worried about bike storage or security, and were left with nothing but a pocket full of access codes.

That is just a tourist experience. If you live and work in the service area, the Citi Bike can change the decision you make every day when you walk out the door to run an errand or meet a friend. Walk for 15 minutes? Bike for 5minutes? Wait for 5 minutes for the bus? Screw it, I’ll just drive? The magic of bikeshare is that you don’t have to worry about the hassles inherent in the “Bike for 5 minutes” choice: you don’t need special clothes, you don’t have to fuss with locks or worry about bringing the bike back with you if you have a multi-stop trip planned. Bikeshare, when working properly, is like having a bunch of moving sidewalks around that can cut your walking time in a third, with no more hassle than walking.

The ease and functionality of Citi Bike relies on several things, though, and New York gets them right.

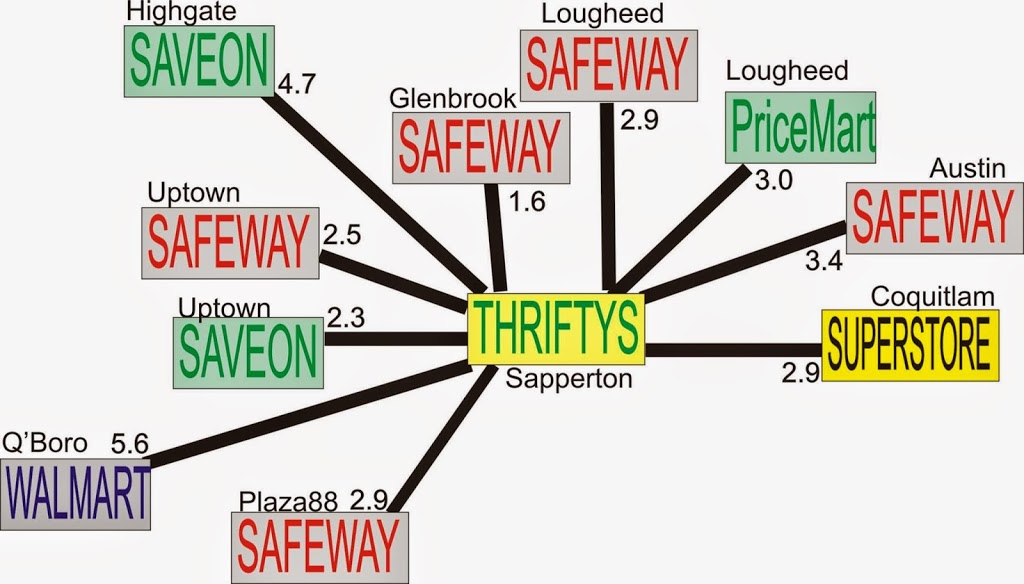

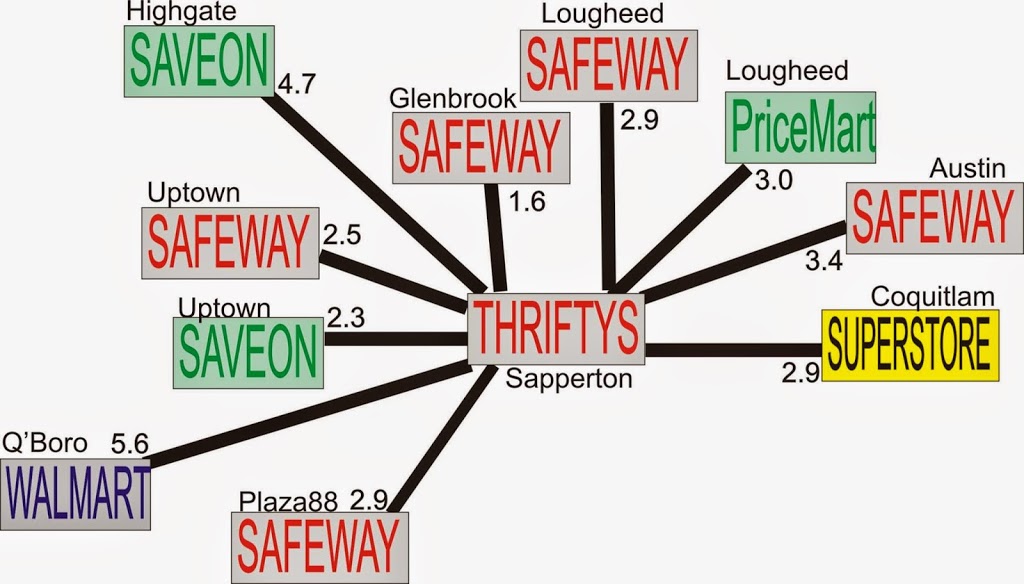

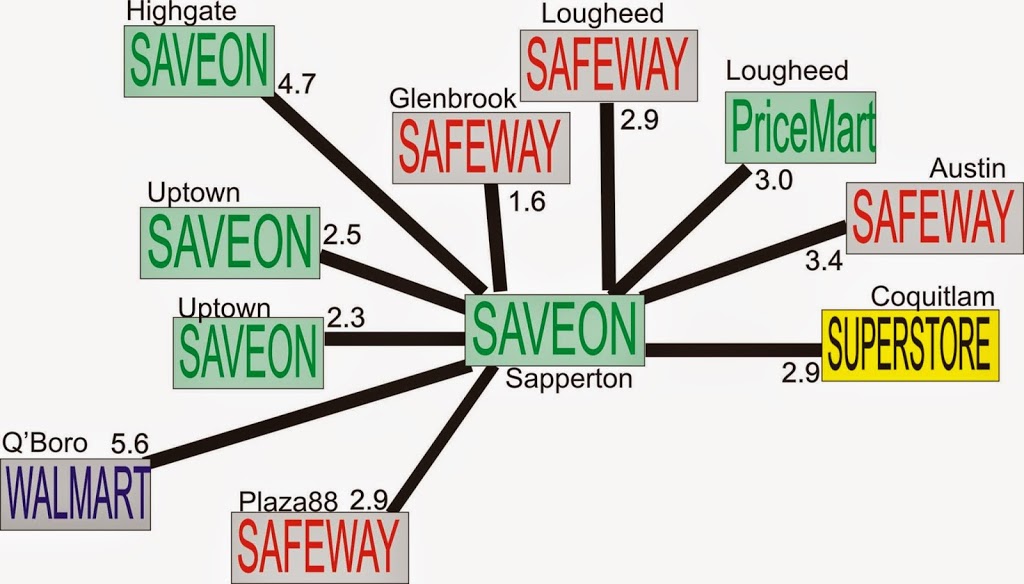

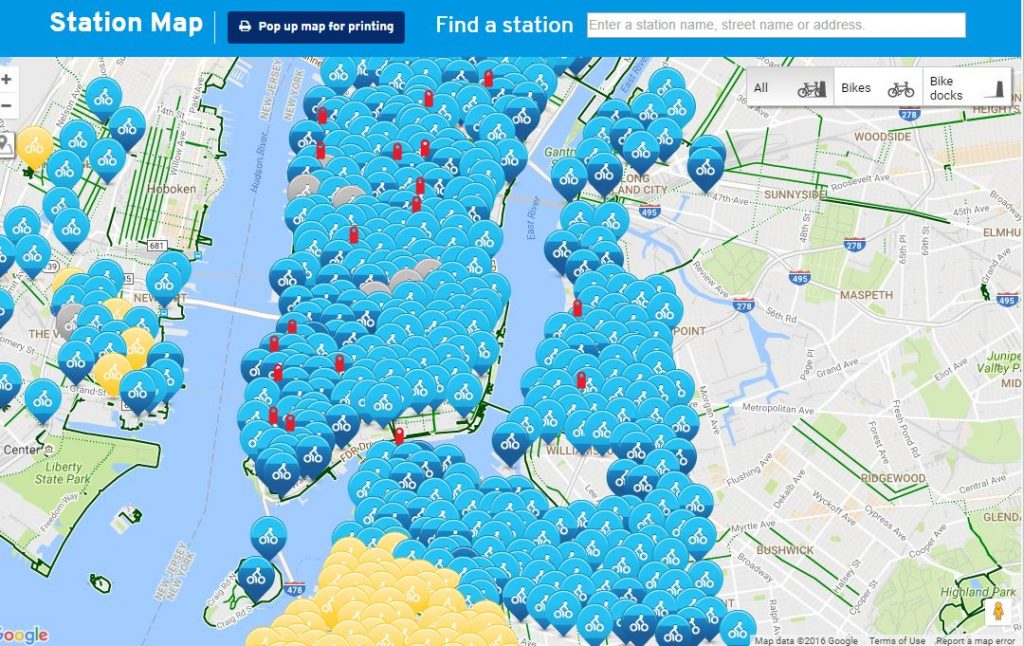

Stations need to be ubiquitous. Within the service area of Citi Bike, you are never more than a 5-miunte ride to the nearest station. They also manage the bikes well, in that I think there was only one occasion when we arrived at a station and found it empty of bikes. Fortunately, the on-line app and maps in the station kiosks have real-time measures of how full the stations are, allowing you to plan at the beginning of your rental. How ubiquitous? Look at the map of Manhattan and Brooklyn:

Bikes need to be Euro. By this, they need to be durable, friendly, simple, and built for casual use. Citi Bike rides are bomb-proof and a little heavy, but run like a Swiss watch. The transmission is internally-geared with a twist-shifter, the chain is in a case, so no grease or oil splatter problems. The wheels have full and deep fenders to keep the spray off, and to keep toes, cuffs, or scarfs out of the spokes. The pedals and seat are wide, flat and grippy so no special clothes are needed. There is a unique-sounding bell, a big basket for groceries, and front and rear lights are always on thanks to the nifty generator in the front wheel. They aren’t specifically elegant, and won’t win any criterium races, but they are the right tool for the job.

The payment has to be simple. Similarly, the kiosks for Citi Bike are simple to use, but have a ton of utility. It takes only a few minutes to buy a day pass using a credit card, and once you are in the system, it takes literally seconds to check a bike out (check in is as easy as park-it-and-walk-away). I could see how an annual passholder would be walking down the street, see a kiosk, and, on a whim, check out a bike to get 6 blocks down the street faster. As a bonus, there are digital maps to show you your location that allow you to zoom out to other station locations, which (as a super-double-bonus) serve as wayfinding tools for all tourists who happen by, not just Citi Bike users.

You can’t have a helmet law. Everything above about the need for the system to be easy, fuss-free, and comfortable is tossed by the wayside when you add helmets. Citi Bike is successful because it accommodates street clothes and on-a-whim decision making. Aside from the (not insignificant) yuck-factor, helmets significantly increase the hassle factor, and change the math on that walk-for-15/ ride-for-5/ wait-for-bus math. The kludged Vancouver solution (ugly, uncomfortable, dirty helmets that are likely more of a choking hazard than actual brain protector) stands in contrast to everything that makes Citi Bike work.

The most significant stat about Citi Bike is that they have, since summer of 2013, had more than 25 million rides, with no fatalities and no major injuries. Manhattan and Brooklyn are not famous for their excellent roads or courteous drivers – the roads are crowded, potholed, and at times chaotic, and Citi Bike users are (reportedly) every bit as chaotic as other users. Many are novice riders, and very few wear helmets. Bikeshare is safer than driving, and Manhattan, it is safer than walking. The statistics are the same for bikeshare systems across North America. Part of this is intrinsic to the bikes: upright, slow, stable, comfortable, and visible. Part of it is the demonstrated phenomenon that the best way to make cycling safe is to put more bikes on the road – areas with bikeshare systems have been found to be safer for those cyclists not using bikeshare systems. Helmets Laws are not only a deterrent to use, they are demonstrably unnecessary for the inherent risk.

So I wish the best for Mobi. I’m not sure there is a sufficiently saturated market outside of downtown and the Commercial-to-Kitsilano corridor to provide the effective station saturation you need to make the system work, but within that area all of the pieces for success are in place. However, until we grow up and have a rational re-evaluation of the province’s silly anti-cyclist helmet law, I am afraid the system will suffer from lack of appeal. And that would be a shame.