Ject asks—

How do zoning and bylaws work in New West? It seems to me that allowing for small retail spaces in neighbourhoods like the ones surrounding Agnes and Carnarvon @ Elliot, for example, would be of great benefit to the community: More walking distance shops and such (I’m thinking coffeeshops, produce stands, maybe a convenience store) would make this area more walkable, livable and agreeable to its inhabitants. I have seen some small stores close to brow of the hill, and I know that there are stores on sixth, but why not more centric?

To answer your first question: it works like zoning everywhere else in BC (except Vancouver), because although the powers local government have under zoning are very broad, they are set out in Provincial legislation. And as in many other things, when it comes to zoning power, the Local Government Act giveth, but the Community Charter taketh away.

There is a lot of talk in urbanist and activist circles about zoning, some even suggesting that it is more trouble than it is worth. There is no doubt the history of zoning is problematic (racist and classist zoning was more the norm than the anomaly for North America for much of the twentieth century), and it is currently a cause of (or at least a functional part of) a lot of inequity in communities. However most don’t really understand what it is as a tool in modern local government.

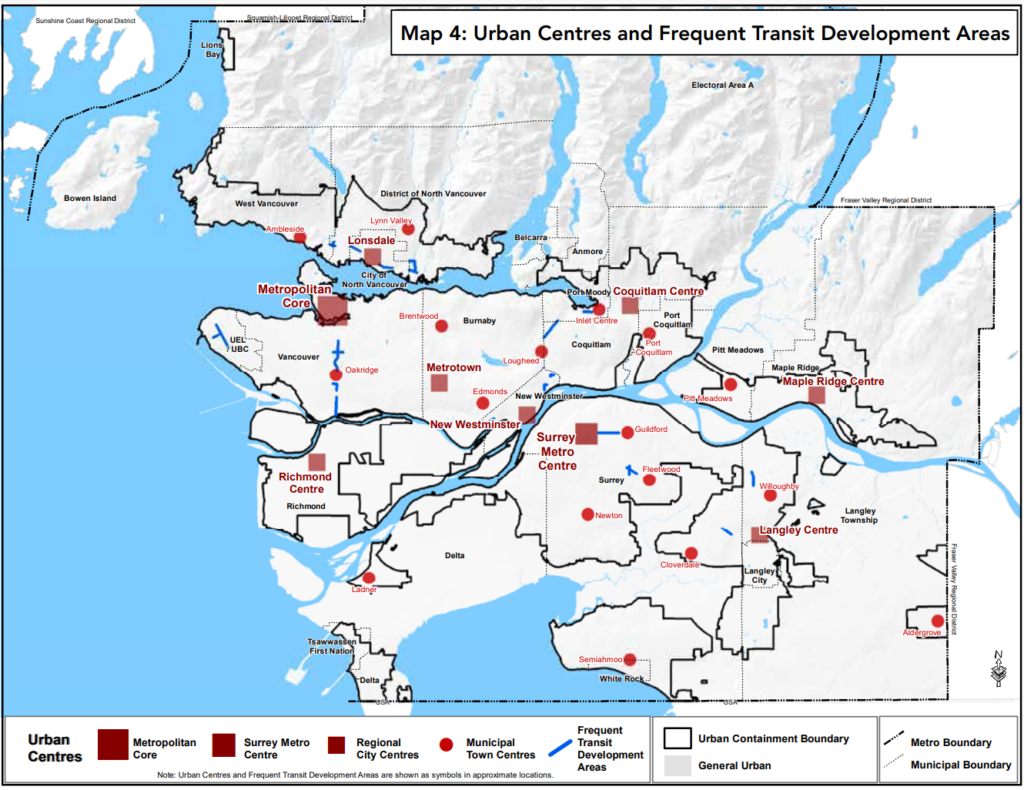

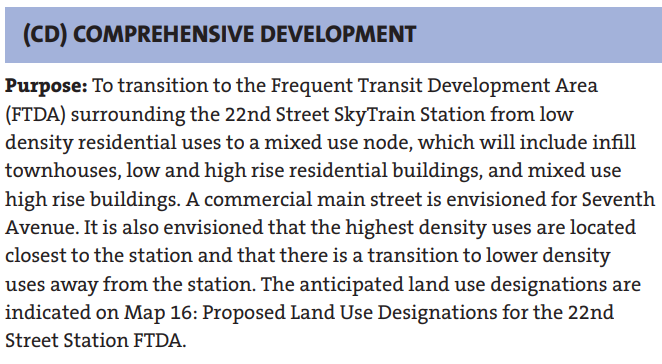

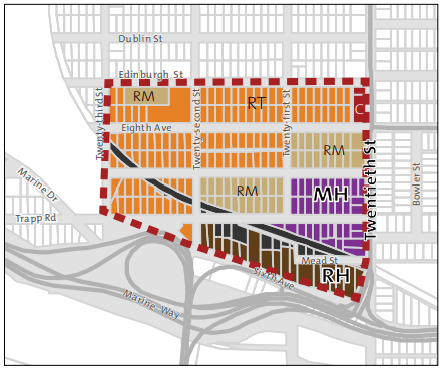

Many armchair planners have a perhaps SimCity-derived thought that zoning is designed to keep noisy, polluting, industries and busy, crowded commercial areas separate from comparatively pastoral and quiet residential areas, so people are healthy and can sleep at night. But in BC, that type of high level distribution of land use is more achieved by an Official Community Plan (OCP). Zoning is a finer-grained distribution of land uses within those bigger categories. It also speaks more to the size, shape, and form of development within neighborhoods, and it also manages more specific land uses and how different land uses are mixed together within the same area. A neighbourhood might be designated Residential in the OCP, but zoning may allow “four floors and a corner store” types of buildings, or even stand-alone buildings that don’t necessarily “fit” the strict OCP designation for the entire neighbourhood, like a stand-alone cafe in an otherwise residential neighbourhood. Map of the OCP designations for the eastern part of Downtown from the City’s on-line map.

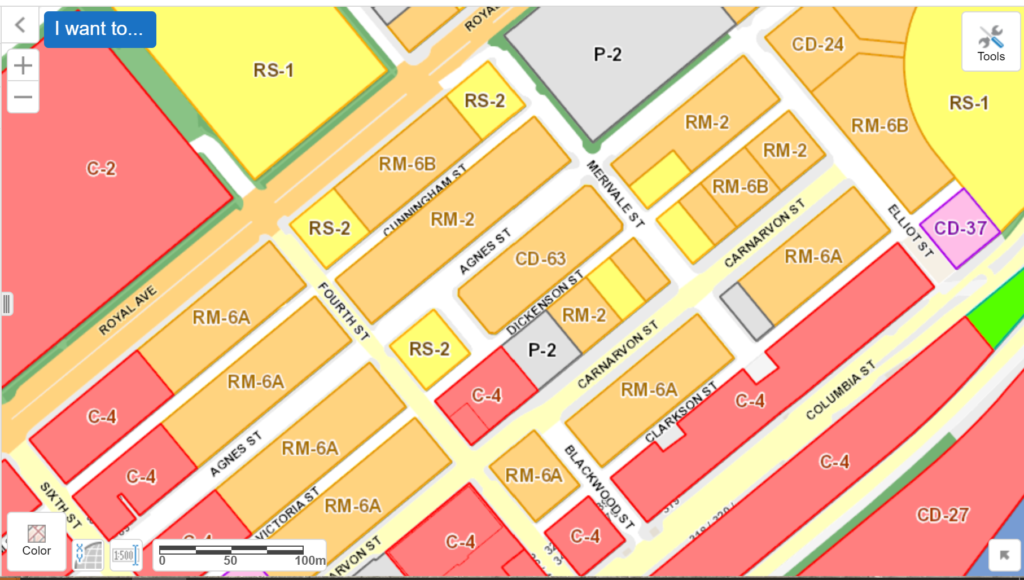

Map of the OCP designations for the eastern part of Downtown from the City’s on-line map.

It’s important to note that zoning doesn’t necessarily drive changes in use, it is usually the other way around. If a specific use is allowed in a zone, it doesn’t necessarily mean anyone will actually come along and do that use, or build a new building for that use. Council rarely re-zones or changes the allowable uses on a zoned piece of land unless a landowner requests it by making a rezoning application – they want to change the use and ask the City for permission.

The thing about zoning is that zoning changes for any lot need to be approved by Council, and (this is the big part) Council can say “no” to a change for pretty much any reason they want. Most powers of Councils are limited by legislation or common law, and we are expected to act reasonably. In administering building permits (as a random example), we cannot capriciously withhold a permit if you want to build something – as long as what you are building meets the zoning and the building code, no bylaws are violated, and you pay your fees. We can’t just say “no” without providing a reasoning for why, and can get dragged into court if we act arbitrarily in refusing you a permit for, say, a bathroom renovation. But if you ask us to change your zoning, we have almost unlimited power to say “no” and you are unlikely to have any recourse.

As a result, a City can ask for pretty much anything in exchange for zoning – Development Cost Charges to pay for sewer, water, and transportation upgrades, so-called “Voluntary” Amenity Charges to pay for other things in the City, we sometimes ask for a strip of land to be dedicated to the City for a boulevard, or sidewalk replacement or other upgrades to adjacent City lands. We can ask the developer looking to re-zone that they build space in their proposed building for Daycare use or Affordable Housing or that they build more (or less) parking, or that they paint their building a different shade of blue. Every rezoning is a negotiation.

Now, this of course is a power a wise Council will not want to abuse. Besides making ourselves unpopular and getting voted out, making rezoning too onerous will cause landowners to scoff at the demands, and no-one will invest in developing your City, which might mean you will not achieve the goals of your OCP. On top of this, the community may lose out on those amenity benefits that could be negotiated. Of course, a Council could cynically use this piling on of demands as a great way to prevent new housing from being built while not appearing like you are opposed to new housing. “This development just didn’t quite do enough to address (pick a concern)” is a great stall tactic that effectively shuts down development as easily as saying no, with predictable results. But as a practicality, most Councils want to make sure the community gets “its share” of the value that the developer receives when a property is rezoned. It’s a balance, and no-one does it perfect.

The point is, if we abolished zoning, we would need to replace it with another tool that provided the community an ability to leverage a fair share of the land lift (the increase in property value that comes with zoning changes in a land-constrained region such as ours) in order to pay for the externalized cost if development and community growth. Right now, it is the best tool we have for that because it is the only tool that gives Local Government negotiating power.

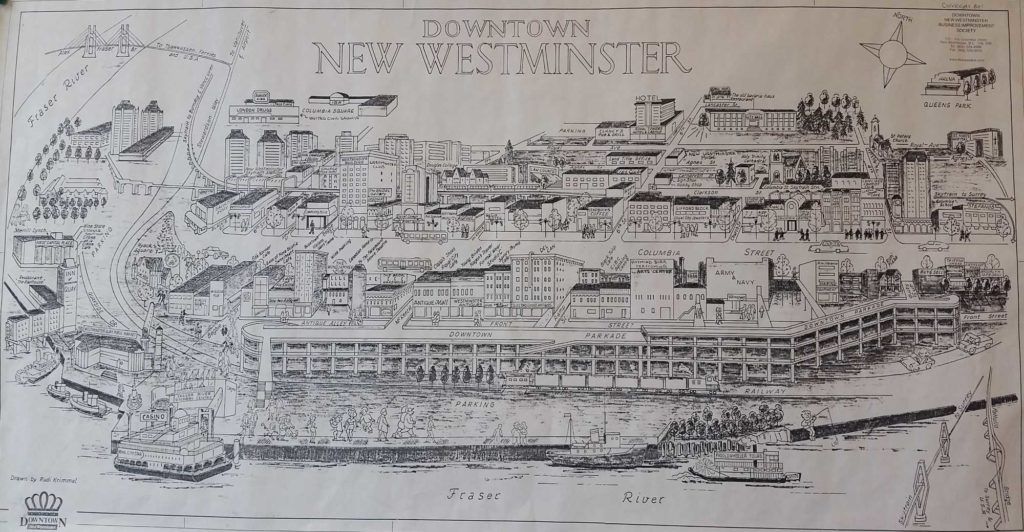

But you were asking about zoning for small retail. This has been a topic of *much* discussion over my 7 years on Council, going back to the last big OCP update. Part of livable, walkable, dense urban communities like Downtown New West is being able to walk to some basic services. I feel fortunate that I live in a part of the Brow of the Hill where I am a <10 minute walk from most services, and as such can do most of my shopping by waking or riding my bike. But there are areas of New West with a paucity of services within such a short distance, like the west part of the West End, parts of Upper Sapperton, or Port Royal in Queensborough. There are also some areas like the east aside of Downtown (as you note) are surprisingly far from some services, and probably don’t achieve the walkscore we would like to see for such a dense community.

Expanding on your example of the east part of Downtown, most of that area (other than Columbia Street, which is commercial) is zoned for low-rise multi-family residential, with a note in the zoning that higher density may be permitted if enough amenity is provided. Any retail coming to this area would need a rezoning. Would Council approve such a rezoning? I don’t know, but I doubt we are going to be asked to any time soon.

There is an ongoing discussion locally and regionally about retail space. I have heard owners of commercial property argue there is too much, and if Cities require retail space as part of new mixed-use developments, they will remain empty, especially as the traditional retail environment has been Amazoned into a state of… shall we call it uncertainty? Others suggest high lease rates and somewhat onerous triple-net lease terms are a result of there being too few spaces available and commercial owners holding all the cards. There is also a universe where both of these are true at the same time, and location and neighbourhood characteristics determine where your street or block fall on that spectrum.

Developers definitely would rather build residential, given the option, because they know the demand is there. Build residential, and it will sell for a pretty easily predicted price per square foot. Commercial space is not as certain. Building a residential property is also more predictable in how you fit it out. Every home needs a toilet and sink in every bathroom, countertops and appliances, wired and plumbed for in suite laundry and known kitchen appliances. But a commercial space is largely unknown. To use your examples, a coffee shop, a produce stand, a convenience store all need very different layouts, plumbing, electrical loads, even locations of doors. So commercial space built on speculation is built as an empty shell, creating uncertain costs for anyone who hopes to lease them and fit them out. I can point you to several places in the city where retail-at grade is still an empty shell years after the residential building it sits on is occupied.

So when the City talked about updating the OCP for the middle part of Sixth Street (between Royal and 4th), the question was raised about whether requiring retail at grade was worthwhile. Perhaps having more residential spaces built will provide better support to the existing retail spaces on Sixth, and zoning for retail grade is making it uneconomic to develop. The same conversation ensued along the Twelfth Street retail strip. Is more retail space needed? If we force developers to build retail at grade, will it be occupied? More importantly, will it make it so hard for a developer to make any money developing the area that nothing gets built, and then the existing retailers don’t have nearby customers. The answer is not simple, and opinions vary.

Where we do see new community-serving retail is in major development projects. Plaza 88 is an obvious example. I think if we were planning Victoria Hill now (instead of 15-20 years ago when the vision for the community was being hammered out), we would include more commercial spaces, and perhaps a few larger retail spaces, though no-one is going to open a major grocery there (with a Safeway and a Save-on each just a little over a km away). That said, the few spaces that are there have taken a significant amount of time finding their purpose. Was that because there are more spaces than needed, or because there are two few to create a real “hub”? The long-proposed “Eastern Node” development area in Queensborough would finally bring some community-serving retail to Port Royal, which is now an established medium-density residential neighbourhood with nary a place to buy an apple. In hindsight, the long wait for this commercial node is really disappointing for the City, and for the residents of that neighbourhood. Hopefully these lessons are being learned and Sapperton Green looks to not only bring more commercial square footage, but is phased to bring it earlier in the neighbourhood development.

So, back again to eastern downtown. To my knowledge, there is only one development in the works in that neighbourhood, and it came to Council as a preliminary application as a mixed use residential, affordable housing and childcare – but no commercial space. For a new commercial space to be built in that neighbourhood, someone would have to come to the City with a plan, and go through a rezoning to make it happen. I cannot predict if Council would support this plan or not, but for the reasons I outlined above, that is just not where the market is for development now, or really where the market is for retail. Neighbourhood convenience stores you do see around mostly have one thing in common – they have been there for a long time and are very low-cost operations. Starting a new one would probably be a financial risk with little chance of recovery. I suspect if you could make money doing it, people would be doing it. So, alas, I wouldn’t hold my breath for any new commercial or retail being built in that area (other than along Columbia) any time soon.