This is not a real “Ask Pat”, but I was recently shown this Facebook Post, and I asked the author if I could answer it at length on my blog. I think it provides a good opportunity to open up a bit of how municipal financing works, from my decidedly non-expert-but-required-to-learn-enough-to-make-decisions viewpoint, and (in a roundabout way) asks what I think is a fundamental question about financing municipal infrastructure.

So here’s a question I’ve been pondering for a while about the housing crisis. I’m not sure exactly when the Local Government Act was amended to change the way municipalities generate revenues to cover the cost of infrastructure to support growth. The current method is called Development Cost Charges (DCC’s).

In conversations with a retired city controller I learned that up to the implementation of DCC’s cities would issue Municipal Bonds to generate the funds needed to cover these costs, build the infrastructure and then taxpayers would collectively pay for the costs through tax payments. In the early 70’s the Province created the Municipal Finance Authority to streamline this process so that hundreds of small communities didn’t have to be floating bonds to generate their infrastructure capital they now have expertise and experience at the MFA.

All this changed with the enactment of provisions in the Local Government Act for DCC’s which are essentially prepaid taxes paid to municipalities to cover the costs of roads, sewer and water installations and parks associated with the new development whether that’s an addition to your house or a 50 storey condo development.

OK so what? Well now the purchase price of that newly developed housing unit comes preloaded with tens of thousands of dollars of prepaid taxes. For arguments sake let’s use $50K as a nice round number, please bear with me for this illustration. So your purchase price includes this $50K, which by the way the developer probably has to finance plus any profit margin the developer might add and so additional costs, but lets work with $50K for now. At 5% mortgage interest that increases monthly payments by about $290 and adds over $37,000 in additional interest to the mortgage. With me so far? Now let’s add property transfer taxes and these days for a lot of people government mandated mortgage insurance as well.

So we’ve transitioned away from publically financed infrastructure growth to growth financed by individual families. What used to be money borrowed at preferential interest rates through government Bonds is now financed by homeowners through their local BANKS, the same ones that continue to report record quarterly profits year after year after year.

So what about the cities. Well since 2008 Canadian Municipalities collectively have managed to sock away over $100BILLION IN CASH while continuing to press Federal and Provincial Governments for cash to help them cover the costs of their suppossed infrastructure deficits. It seems to me that while its easy to blame ‘foreign investors and speculators’, at least some of this crisis needs to be laid at the feet of our governments at every level.

My first impression is that this discussion conflates a couple of things, and that is leading to a bit of confusion. Here is my understanding of the relationship between DCCs, Municipal Bonds, and the MFA.

The idea behind DCCs is to charge the capital cost of infrastructure expansion to the persons who benefit from that expansion. DCCs are charged when there is growth in residential density (a 3-story building becomes a tower, a house becomes a set of townhouses), and are meant to assure that a fair share of the cost of building bigger sewer pipes, bigger water pipes, buying new parks space, etc. is covered by the new population that fills that density. The City charges a DCC based on the square footage of the new density, and presumably the developer passes that cost onto the purchaser of the property, who is the ultimate beneficiary of the new infrastructure. In New West, we have DCC Bylaws for Transportation, Water Supply, Sanitary Sewer, Drainage, and Parks.

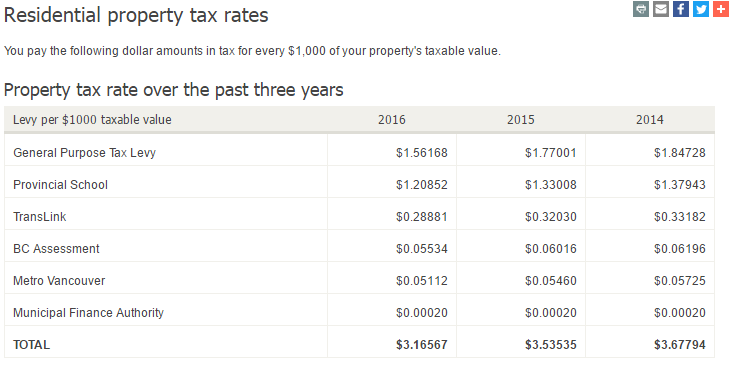

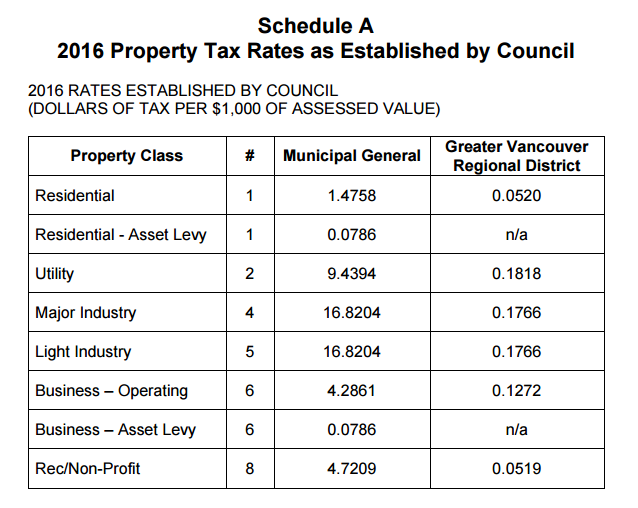

At current rates, a new 1,000 sq ft apartment in Downtown New Westminster would include about $5,140 in DCCs. That would be $1,120 for Transportation, $60 for drainage, $250 for water, $430 for sanitary sewers, and $3,290 for Parks. Note than a brand new 1,000 square foot apartment in New Westminster sells for something over $700,000. If you believe that the cost of new housing is directly correlated to the cost of building it, then DCCs can be said to raise the cost of any single unit by much less than 1%. Although they cumulatively do a lot to reduce the cost of infrastructure upgrades for current residents, I don’t think DCCs are a significant cause of the current housing affordability crisis.

It is important to note DCC money is not thrown into general revenue, but is put into specific reserve funds and earmarked for defined projects under the category for which they are collected. This is fundamental to the DCC regulation – they must be spent on improving infrastructure above and beyond what would have been spent if the density was not permitted.

For obvious reasons, DCC money is not spent the day it is collected. A City is a complicated thing, and we cannot upgrade a section of sewer on a whim. Instead, we need to plan out years, sometimes decades, in advance so that all parts of the system work together. When collected, DCC money mostly goes into a reserve fund and is drawn out when the works happen. Sometimes we can borrow against a reserve fund (if the sewer needs to be upgraded today, but a DCC has not been collected yet and we are confident it will be collected in the near future), but even that is a bit deeper than we need to go here.

DCCs also don’t pay for all infrastructure upgrades. Even if there was no density increase in a City, we would have to replace your water lines every 50 years or so, pave your road every 10 years or so, etc. That money comes from property taxes (in the case of roads and parks) or part of your water/sewer bill (in the case of the pipes). We collect a little more in your water bill than it costs us to run the water system, and set that aside into those same reserves to pay for maintenance and upgrades of the system when they are needed. Alternately, we can pay for the upgrades when they come up by borrowing money, and charge future users that cost (plus interest). As you will see, we do a little of both based on what makes the most financial sense at the time.

That is how we can have both $120 Million in our reserves and $65 Million in debt. I hate using household finances as a model for explaining municipal finance (they are two very different things), but this is similar to having money in an RESP account at the same time as holding mortgage debt: we do it for rational reasons related to how the financial and taxation systems are designed. We didn’t invent global capitalism, but we operate within it. If you have an alternative system that more fairly distributes capital, send me your e-mail and I’ll subscribe to your newsletter!

This does raise what I think is the fundamental question about how we finance public infrastructure. If we want to build, say, a new $100 Million recreation complex, do we save up enough money to pay for it before we build it, or do we build it on debt and pay it off over time? There are compromises to both.

In the first case, everyone pays today into a reserve fund until we hit the number that we need to build the complex. It will take several years, and for all that time, the taxpayers of the City will be paying into the fund but not receiving the benefit of those payments until some point in the future when the complex is completed (if they still live in the City at that time). Is that fair to them?

In the second case, the complex gets built first, and the people who have an opportunity to benefit from that complex pay taxes for it while it is being used. Of course, they have to pay a little more this way because the debt needs to be serviced over the period of time it takes to pay it off. Is that fiscally prudent?

(It sounds to me like you would prefer more of the latter in the case of financing infrastructure related to new growth, as it would result in the City borrowing more from the MFA or Municipal Bonds and spreading the cost evenly among all taxpayers, whereas the former puts more burden on the new home purchaser which they would, presumably, borrow from a bank to finance. Please correct me if I got your argument wrong.)

There are other factors that need to be considered, and this is why most local governments do some combination of both. It matters what interest rate a local gov’t can earn on its reserves vs. what interest they pay servicing the debt. In this low-interest era, we may choose differently than back in the high-interest 70s. These rates are also related to your financial status: a City with $100 Million in the bank can get a lower rate than a City with $100 Million in debt. There are also significant complications local governments have to go through to borrow beyond their 5-year financial plan. Add to this uncertainties like inflation of construction cost and other capital needs that may pop up in the same time period. The practicality is that we sometimes need debt, and we benefit from strong reserves.

I don’t want to get into the discussion here about us going to senior governments with hats in hand asking for their help in funding public infrastructure (this blog post is already much too long). However, I can summarize by saying local governments are responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of about 60% of public infrastructure in Canada, and we directly receive about 8% of all tax revenues. Without help from senior governments, little of your public infrastructure would be sustainable. The Infrastructure Gap commonly measured across Canada to be more than a hundred billion dollars is measured above our existing reserves; but I digress.

The Municipal Finance Authority is, essentially, a Credit Union. Local Governments can borrow money from the MFA at rates better than we can get from commercial banks, and we can save our reserves with the MFA and receive a pretty good return. Most years, New West makes a little more in interest on our reserves than we spend in interest on our debt (though market fluctuations obviously impact this equation). As you note, the MFA structure has largely replaced Municipal Bonds issued by individual Local Governments. In essence, the MFA issues Bonds on behalf of all its member Local Governments. I am really not an expert on this part of finance, but I would assume that the reason we use the MFA instead of issuing our own Bonds is that the interest rates the MFA can offer (because they are a large, diverse organization) is much lower than we would have to pay to make the Bonds attractive in this razor-thin investment market.

But perhaps more to the point, the Bonds vs. MFA issue is something completely separate from the DCC discussion. DCCs are taxation – they generate revenue for a Local Government. Bonds are simply debt instruments; they are loans which we would have to generate revenue (taxes) to pay back. This takes us right back to the fundamental question that we have already asked – when should a government collect the money to pay for new infrastructure? Before it is built, or after? In reality, we do a little of both, and use the financial instruments available to us under the Local Government Act to hopefully strike a fair and responsible balance between the needs of today and the needs of tomorrow.