Assessments are here. For those who own homes, this means a letter arrived in the mail telling you what the assessed value of your property was on July 1, 2019. It also tells you what the assessed value was over the previous three years. Some people are very upset to find their property has gone up in value, which means their property taxes are going up. Others are very upset that their assessed value has gone down, and their investment is losing value. At least, that is what I glean from Social Media, but maybe I need to get out more.

I have written before about the relationship between property assessment and property taxes, and about how the assessment process works, so this will be a bit of an update/summary of those posts. A bit of redundancy, but with new numbers.

First off, your assessment does impact your property taxes, but not as directly as you may think. The City has not passed a 2021 budget, so I do not yet know what the 2021 Property Tax rates will be, but in our last discussions, we seemed to be settling towards something like a 4.9% increase over 2020. I will round that up to 5.0% for the purposes of this discussion as long as we can all agree that is speculative and the numbers may change between now and when you get the bill.

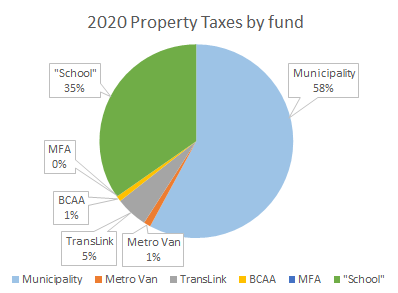

That 5% means the amount of revenue the City will receive in property taxes from existing taxpayers will go up 5%, but it does not mean the cheque you write in July will necessarily be 5% higher than the one you wrote in 2020. First off, it only impacts the portion of property taxes that the City gets to keep. Last year, your residential Property Tax Bill looked like this:

So 58% of your property tax goes to the City, 35% to the provincial government through the School Tax, and about 7% to other agencies regulated by the provincial government. Everything else I talk about below here relates only to that to-the-City portion of the tax bill. To find out how the School Tax is set or how the BC Assessment Authority spends it’s 1%, you need to go to someone else’s blog. All this to say if the City put your municipal property taxes up by 5%, the amount of money you pay only goes up about 2.9% (that is, 5% of 58%).

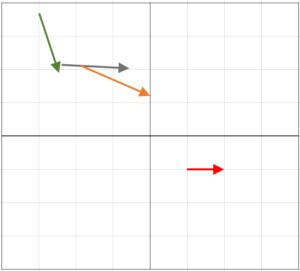

If you look at your Property Assessment letter, you will note that the average change in property values in the City of New Westminster was a 3% increase. Because the City calculates its property tax rate based on this average value, a 5% increase will be based on this value. If your house went up in value by the average, then a 5% tax increase means the municipal portion of your property tax bill will go up 5%. The relationship between these two numbers is linear, so to calculate your potential increase, subtract the average value increase from your own value increase, and add the 5% increase the City is proposing:

My assessment (1940 SFD on a 5,300sqft lot in the Brow) actually went down by 11% since last year. So my Municipal taxes would go down by (-11)-(3)+5= –9%.

My friend in Sapperton (1920 SFD on a 4,000sqft lot) saw her assessment go up by 20% over last year, so her Municipal taxes would go up by (20)-(3)+5= 22%. Yikes.

Assessment is a dark science, and every year there are weird local effects of property values in one neighbourhood going up or down relative to others, and it is not always clear what the causes of these changes are. A recent example is the Heritage Conservation Area in Queens Park which was either going to cause housing prices to go through the roof and make the neighbourhood forever inaccessible to young families, or was going to crater the value of the houses dooming young families to inescapable debt, again depending on which Social Media account you followed. The reality is, it had little perceptible effect when compared to similar properties in Glenbrook North or the West End over the last 5 years. The market is bigger than one neighbourhood.

Properties actually sell “above assessed value” or “below assessed value”, a metric that is often used as an indicator of a market trend, since assessments are always at least 6 months old. However, it is important to remember that, in aggregate, things just don’t shift as much as they do in one-off conditions. If the person up your street who spent $50,000 on a new kitchen sells their house, they are likely to get more than the neighbour who has a black mold farm in the basement, even though both houses may look the same from the outside. Assessments are approximations of how the “typical” or median house of the size, age, and lot dimensions in your neighbourhood should be valued, not an evaluation of your wainscoting. Individual results may vary.

If you think your increase or decrease this year is unfair, there is a process to appeal your assessment, but you can’t dawdle. Local governments have to know the official assessed values by April so we can set our tax rates and get those cheery bills into the mail, so the Assessment Authority has to provide official numbers by the end of March. Therefore you only have until February 1st to file an appeal, but if you think you might want to do so, you should contact BC Assessment immediately and get the details about what you need in order to make that appeal. The important part is that the onus is on you to provide evidence that the appeal is wrong, not vice versa.