As I mentioned in my last Council report, we had a presentation on the first annual evaluation of the Crises Response Pilot Project. I don’t usually report out on presentations here (there was no decision for Council to make), but this one led to some interesting discussion and is centre of mind for many people in New Westminster. It is worth taking the time to unpack the report a bit, it had both good and bad news.

For those folks new to the scene, the Crises Response Pilot Project is a collection of actions and resources meant to address the three overlapping crises impacting New Westminster and communities across the province in the echo of the pandemic: homelessness, untreated mental health conditions, and a toxic drug supply. Like Many cities, we were putting a lot of resources into clean-up and “public order” responses, and were into making progress, while staff got more overwhelmed and the community got more frustrated. It was clear doing more of what we were doing wasn’t going to get us further ahead.

Working with the province, the health authority, non-profit providers and the broader community, The City adopted a three-part pilot project, the details of which you can read about (or watch the video) here. We also committed to having an external evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the project, and to let us know what is working and what isn’t. Last meeting we received our first report from that external evaluation.

Dr. Anne Tseng, a Sociologist from Douglas College is the person performing this evaluation work, and also used hew academic expertise to develop the evaluation goals, metrics and methodology for analysis, and as some of those were challenged by members of Council during last week’s meeting, I felt it important to remind them that these metrics were agreed upon unanimously by Council back in April. It is frustrating and counterproductive to attack a person working for the City for doing the very thing Council asked her to do. But such is politics today.

“The pilot project is designed to be trauma-informed and people-centered in responding to individuals with lived and living experience of the harms associated with the three crises. Furthermore, the pilot project also incorporates strategies to address the externalities of the three crises that have spillover consequences for residents, businesses, and interest-holders in the community.”

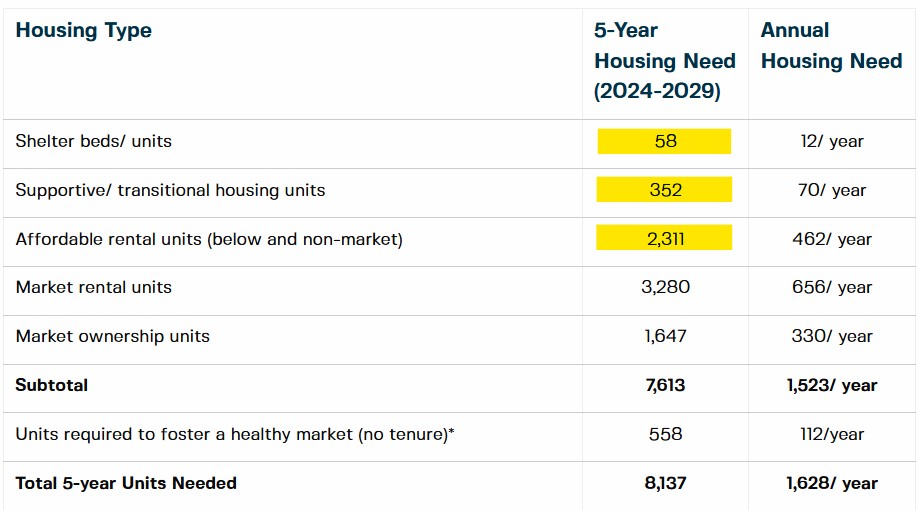

There is good and bad news in this report, but there are also recommendations to improve data gathering and progress tracking, and recommendations to improve upon the deliverables. There is the raw data in here that tells one story, such as the hundreds of referrals to health services, including IHART and ICM, and the 135 applications to transitional and supportive housing that CRPP staff have helped facilitate. There is also, unfortunately, a bottleneck in transitional and supportive housing that means most referrals are not resulting in people getting into a housing stream. The completion of 52 units of housing at 6th and Agnes will help significantly with this, but it is still under construction, and the need for shelter services will remain unabated until housing investments ramp up to meet the need.

The operations team have also been effective, and we are receiving positive feedback from a lot of residents and businesses downtown that the streets are much cleaner and better maintained in some “trouble spots”, but we are not around the corner completely on this, and it is still a place where significant resources are being spent.

The Community Liaison Officers are responding to calls (you know about the One Number to Call, right?) and addressing issues, but increasingly they are being proactive – getting out to problem areas before the complaints or concerns come in, and again we are starting to receive some positive feedback from the community on this work. Most concerns are related to encampments and tents, and I again refer you to the point above about the desperate need for safe accessible shelter space in the short term, and more robust housing investments in the medium term.

One part of the report that is strong on recommendation (that is, where we are falling short) is where we are not effectively getting the information about this project out to residents and businesses. Simply put, not enough people know about the program, and are still asking “what is the City doing about all this?” It is also clear that in the absence of good information, misinformation inevitably fills the void. With a topic as politically charged as this one, fear and stigma are amplified through that misinformation.

“…residents mentioned the stereotypes and stigma attached to individuals experiencing the crises and the need for better education and awareness to combat misinformation. Several participants also mentioned the need to not only spread awareness but to foster empathy and understanding. A participant attributed misinformation to the media, which they described ‘drives fear and feeds into stereotyping.’”

Council has heard clearly from downtown businesses that the false narrative being presented about downtown – that it is a dangerous place where businesses are failing – has been harmful to both businesses and to people needing support. It is incumbent on all of us to fill that fear-based information void with good information about the work being done.

On the good news side, the communication upwards to senior governments has brought positive results. Advocacy to the Ministry of Housing and Housing BC has created better staff-to-staff collaboration, investments to improve shelter services in the City, and ongoing work to develop the next phase of supportive and transitional housing. Similarly, the advocacy to health partners has brought increased and improved resources to the City, including collaboration toward an adult Situation Table (to coordinate resource supports in a client-focused way).

We were able to recently announce that our original $1.4 Million grant from the federal Emergency Treatment Fund has been enhanced with another $290,000 grant from the same fund. This demonstrates that the Federal Government recognizes we are doing something innovative and proactive here in New Westminster that will ultimately save the health care system more than this ETF contribution, while building community resiliency. The Federal Government is noting that New Westminster is taking a more proactive approach to the same challenges that are impacting communities across Canada, and that the model of inter-governmental and inter-agency collaboration we are showcasing here is scalable to other communities facing the same challenges.

This report comes as the CRPP is still in its initiation phase. We have a lot more work to do, and we are continuing to measure our work so we can adapt as the need on the ground requires. Having an external evaluator hold us accountable to the community, and to our funders, is an important commitment we have made in launching this pilot.

I’m really proud of the work staff in the City and our partner agencies are doing, and am proud of New Westminster residents and businesses in supporting us in this approach. This is what it means to live in a City that is a community.